By Jan Worth-Nelson

I just lost my temper. The trigger was an early morning solicitation to subscribe to the Flint Journal — our hometown paper, right? I asked the young voice with a Southern accent where she was calling from. Missouri, she said.

Missouri?

“Missouri?” I shouted, “I want nothing to do with a newspaper in my home town that outsources its business to another state!” And I hung up.

Okay, so it was an overreaction. For one thing, you should never wake up retired geezers when we’re sleeping in. It’s a luxury we’ve waited 50 or 60 years for.

And I understand that the Flint Journal’s survival in any form is a sad miracle of cutbacks, compromises and consolidations. While much of the business aspect has been farmed out, there still is a reporting staff in town.

But I’m touchy on how all this plays out. I love local news. And I’ve been shaped by my own history in journalism.

Keokuk, Iowa shaped my views

After the May, 1970 shootings at Kent State, where I was a journalism major, I fled by bus from Ohio to Keokuk, Iowa, where I had convinced the crusty old-school editor of the newspaper there, the Daily Gate City, to take me on as a summer intern.

It was a perfect destination to satisfy my quest for adventure. Perched on the bluffs of the Mississippi River, it was home to a set of locks traversed by the commerce of the whole breathtaking river.

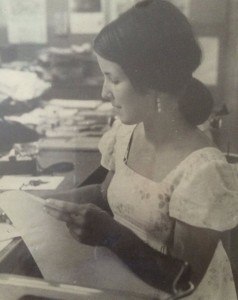

My mentor and guide was Eleanor Waterhouse, a spirited city editor not much older than me. She was recent graduate from the University of Missouri School of Journalism.

She curtained off a corner of her walk-up apartment in an old Victorian, installed a fold-up single bed, and there I stayed until September. For the summer we were almost inseparable. She pulled me into the life of a small-town journalist, letting me cover anything I wanted. I learned to work on deadline, write an “inverted pyramid,” and ask hard questions. It was a blast.

Ellie Waterhouse dropped in to visit me recently in Flint. It has been 45 years and we’re both retired and matronly now. But we still love our memories of the Daily Gate City and our devotion to covering local news.

I spent five more years at two other newsrooms before heading off to other escapades. But the imprint of those newspaper days has never left me.

Why do I care?

If Gary Custer hadn’t died, maybe I wouldn’t care today, but now that he’s gone and I’m an old woman come back unexpectedly to a business I have loved all my life, I find myself taking seriously what journalism owes to its “place,” whatever that is.

It matters to me that reporters who cover Flint locally live among us – or at least, like Teardown author Gordon Young, have a sense of the place. I want to know that they worry about their water, try to decide where to send their kids to school, try to find a grocery store, negotiate down bumpy brick Saginaw Street, wait in line for the pho at MaMang.

I was a Flint Journal subscriber for more than 25 years. I finally cancelled when the paper shrunk to four days a week, lost most of its reporters, shut down its local presses, and moved out of its venerable 150-year-old building.

I confess I miss the plop of the paper on my porch in the early morning – an archaic comfort from a past life, the trace continuity of a slower-paced, civilized community.

We need good local reporting

But there’s more to it than that. The recent water crisis is an important example of why we are thirsty, one might say, for thorough local coverage. As I’ve said before, the Flint Journal’s Ron Fonger did a great job of following the complexities. But many of us found that wasn’t enough.

People became reporters on their own — pressing politicians, digging into the minutes of local meetings and documents, researching water quality issues, lead effects, proper filters, the design and dangers of the pipes underneath us, the chemistry of corrosion.

And we shared all this with each other, sorting out the facts and lies just like a good journalist would do. Maybe that’s the way it should be. But I still crave the role of the Fourth Estate, and I worry that it’s slipping away.

I decided to visit the physical Flint Journal – the version with doors and windows and people I could talk to face to face. I’d never been there since it moved – a sad comedown, I thought – three years ago.

I wanted to see if there was any “newsroom” left, if there was anybody “local.” I wondered if there might be some old editor chomping on a cigar and yelling at the reporters, a half-drunk columnist with a hangover asleep in the corner, impossible piles of papers and crumpled coffee cups littering the floor.

Flint Journal now: a storefront

Well, there is a there, there and a who there too. The Flint Journal office, now a storefront on Saginaw Street sandwiched between a packaging company and an art gallery, is shiny and modern. Behind a reception desk are rows of uncluttered tables with people plugged in, focused on laptops.

There I found Bryn Mickle, the paper’s editor since last year. At 42, he rose through the ranks after arriving as a reporter in 1999. He took over the Flint edition after the previous editor moved into an executive role with M-Live. He lives in Grand Blanc.

The reporting staff has been sliced from about 50 in the old days to a core group of about 10; of those, two are crime reporters, one is a court reporter who helps cover crime, and one is a sports reporter.

The hard copy is printed in Walker and Bay City. And of course most of the action now is online, where MLive, part of the Newhouse family of national publications, has an active presence and readers click on whichever city they want for local news.

Mickle remembers when the paper was printed at the corner of First and Harrison. When the presses started up, he recalls, you could feel the whole building rumble.

No liver sandwiches

But as far as going back to the glory days, when the print run of the Sunday Journal was about 100,000, “Well,” he said, “there’s a reason McDonald’s doesn’t offer liver sandwiches — the demand isn’t there.”

Mickle said he didn’t know the size of the current print run, but 2012 numbers put subscriptions on the weekday edition at about 50,000.

“We are not a newspaper with a website,” Mickle said. “We are a website with a newspaper.”

Staff cuts mean that the local crew has to be very selective. Many coverage decisions are driven by metrics – analytics that tell Mickle how many people click on what links. Despite what people might say on a survey, he said, the Journal’s data supports the old journalistic cliché: “If it bleeds, it leads.”

Backpack, phone, laptop

Mickle doesn’t have an office, not to mention a desk. Nor do any of the reporters. When Mickle greeted me he had to find a conference room for our conversation — a pristine space with not a single pile, messy ashtray or bookshelf. The newsroom on Saginaw Street is designed around an “open concept.” Nobody has an assigned place to sit.

“Everything you do is basically contained in your backpack,” he said. Each reporter gets a cell phone and a laptop and together, those three tools are their offices and their desks.

“It’s a freeing concept for me,” Mickle said. Like most journalists, he said, he was a pack rat, but has learned the liberation of traveling light. Whatever he wants to keep he scans onto his laptop.

No more cubicles

Scott Atkinson, a former Flint Journal reporter now teaching writing at the UM – Flint, said he loved the open format. He said it helped him grow as a reporter.

“The idea that a reporter should show up to the office every day and sit in his/her cubicle was gone,” he said. “I worked at Good Beans, the Crepe Shop, the Flint Public Library, the Flint Institute of Arts café, the passenger seat of my car.

“People and I talked about the issues of the day, our kids, our city. I probably walked at least a mile a day.”

The Journal’s archive – what used to be called the “morgue” in my day — is maintained at the Buick Gallery of the Sloan Museum, and all issues since 1997 are on the Journal’s electronic library. Yes, it’s an extra step for reporters to dash over to Sloan, Mickle noted, but the museum helps out when immediate access is needed.

So even though my nostalgic craving for that old newsroom durably nestles in memory, it seems the current era offers unparalleled – and changing – ways to be ‘local.” It seems we can be “local” from almost anywhere – and even in town, reporters now are much more likely to leave their little storefront and find Flint stories.

I’m not here myself

Here’s the thing – I saved my kicker for the end, while I was finding out what I wanted to say. As many readers know, a third of the year I’m not even “here” myself. While I’m finishing this column in my den on Maxine Street, I started it in Los Angeles, where I live from time to time.

In fact, my husband and I put together our last edition of East Village Magazine – the one obsessed with Flint’s water debacle – from a small apartment on a San Pedro hillside. It’s our laptops, cell phones and a speedy Wi-Fi that make it possible — with the essential help, of course, of a staff of volunteer “citizen” writers who faithfully show up – in person — at neighborhood events and meetings.

So even though I myself, like the M-Live crew, rely on my backpack, cell phone and laptop to keep in touch, I confess I’m still a romantic about my journalistic sense of place.

I much prefer the sound of those CSX trains as I bang out columns, the fragrances of fireplace smoke this time of year, the actual cappuccino at Steady Eddy’s. Now, where’s my cigar and that half-full bottle of booze? It’s deadline time.

Jan Worth-Nelson is the editor, since January, of East Village Magazine – a late in life career surprise she never asked for and never expected. In addition to her summer at the Keokuk, Iowa Daily Gate City, she worked at the Laguna Beach (CA) News-Post and the Orange Coast Daily Pilot.

You must be logged in to post a comment.