By Robert R. Thomas

By Robert R. Thomas

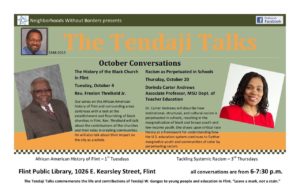

The effects of capitalism and how racism is perpetuated in schools were topics explored in a recent Tendaji Talk at the Flint Public Library by Dorinda Carter Andrews, an associate professor from the Michigan State University Department of Teacher Education.

Drawing on the work of critical race theorist Derrick Bell, Andrews suggested to a group of about 15 that because it is based on a system requiring winners and losers, capitalism is an inherently racist system and that education has been a “project of cultural imperialism.”

A former K-12 teacher in public, private, and charter schools, Andrews came to her passion for equitable educational systems through her mother, a teacher, and as a student in her native Georgia where she participated in a voluntary program that bused black students to predominantly white schools to racially diversify those schools.

Eventually Andrews’ practical educational experiences blended with her interest in theoretical frameworks of systems.

“I consider myself a race researcher,” Andrews said. Her specific focus is marginalized youth of color and poverty who are the detritus of structural, cultural and institutional discrimination.

She explained that researchers “use theoretical frameworks and try to bridge theory with practice to better understand how we can improve practice.”

“I’m going to be talking about how institutional, structural and cultural racism is perpetuated in schools, and using critical race theory as a framework for us to understand that,” she added.

Critical Race Theory (CRT), she explained, is a theoretical framework used in the social sciences focused on a critical analysis of society and culture where race, law and power intersect. The concept began with Derrick Bell, a law professor, and was later adapted from legal practice to studying systemic racism in education.

Andrews said that a major tenet of CRT is that institutional and interpersonal racism is a function of structural racism.

“Structural racism,” she said, “is a system of hierarchy and inequity, and it is primarily characterized by white supremacy.” All racism derives from structural racism, she asserted, because the system is one enacted by whites to advantage whites. “You have to think about racism as a systemic problem,” she said. “If you get stuck at the interpersonal level, you cannot solve systemic problems.”

Historically structural racism goes back to slavery and school, according to Andrews.

“Labor force and capitalism drives the way we do education,” she said.

“And capitalism in and of itself is racist. I’ve been called a socialist plenty of times, but if you think about capitalism as a system, it’s inherently a racist system; a classist system; an inequitable gender system. There have to be winners and losers….And so all our institutions, education being one, are operating in an inherently oppressive structure based on white supremacy where whites are always to be advantaged in the system.”

Andrews defined institutional racism as “discriminatory treatment usually manifested through unfair policies, and inequitable opportunities and impacts based on race, produced and perpetuated by institutions.” The key word in the definition, she emphasized, is “policies.”

Cultural racism in the educational institution Andrews described as being “like cultural imperialism in school. It’s the universalization of the dominant group’s experience, culture, their way of life. It’s the norm.” Her historical educational example was our government’s policy to send indigenous American people to the boarding schools for a better way of life.

“It was basically a project of cultural imperialism,”she said. “Racism in this country is not just a black and white issue….If we think of any dominant category, that’s the cultural norm that has been imposed on everyone. And it is a white supremacist cultural norm.”

Another tenet of CRT Andrews examined is a concept called “interest convergence.”

“Derrick Bell believed,” she said, “that the interest of particularly blacks, in gaining racial equality in the U.S. are only accommodated when whites see benefit. That’s called ‘interest convergence.’ And I want you to think about how that might happen in education—that there are gains made for people of color only when the dominant group sees that it’s a gain for them. Otherwise, we’re going to slow this train down. If we can’t see a benefit for us, we’re not going to help those who are subordinate to us.

“Another tenet of CRT,” Andrews said, “is that it is important to illuminate the voices of marginalized people. We don’t hear the narratives of people of color enough. We talk about what’s better for kids of color in schools; we don’t ask them. We need to do more talking with them to understand their lived experiences in schools and how we can best accommodate them.”

Critical race theorists also understand that race intersects with other identity markers in our schools.” For example, she asserted that a Latino male’s experience is not the same as an LBGT youth of color in our schools. CRT calls this tenet intersectionality.

Closely aligned is another tenet, anti-essentialism. Andrews’ example is “black boys…as if that is a monolithic group with the same lived experiences. We have to understand that that’s dangerous territory when we say, Here the teaching strategy is for black boys. Well, there are different kinds of black boys.”

She added that “we should not essentialize white folks; white folks are a very diverse group. Again, we’re talking about a system of oppression. The participants of the system are diverse. The system is what has maintained itself over time. We all participate in the system; you just have to decide how you are going to participate. Are you an oppressor, or are you someone who is empowering others in fighting the oppression?”

Having set the CRT framework, Andrews returned to how racism manifests itself, specifically in education, according to these tenets.

“Much of the research says our schools are actually more segregated now than 40 or 50 years ago, she said. “There is a big difference between racially desegregating school spaces and achieving racial integration, “ she said. “And the project of integration, many would argue, has never been realized in education. And what has led to that? A continual project of structural racism that is located in the historical, the economical, the cultural. The institution of education has just perpetuated it through policies.”

Andrews emphasized that she wanted us to understand racial segregation as not just institutional, but something structural happening in education.”

Andrews spoke of how underfunding in U.S. schools gets perpetuated as a function of institutional racism.

“Inequity in school funding underscores the function of racism prominently in schools. It is a function of institutional and structural racism,” she said. “Part of the problem is that we work too long trying to fix educational problems in a vacuum. You can’t do it because all these institutions are connected. But we just expect schools to fix the problems.”

The underfunding of poorer school districts, Andrew argued, is “state sanctioned violence, that it is the responsibility of those who we have elected in power to redress these issues in our schools. But they allow and perpetuate institutional racism by allowing this to go on.”

Andrews then used her research to debunk the effectiveness of such policies as charter schools, no child left behind and tracking children early in their educational experience.

“Look,” she said, “these charter schools, there’s no research showing that they are actually improving things for black and brown kids.”

Andrews points her data at the fact that for every charter school success story the media portrays, there are thousands of underperforming charter schools across the country.

“But it’s not white kids populating these schools,” she said, “it’s black and brown kids living in working class-being-right-on-the-edge-of-poverty conditions and those living in poverty.” With charter schools, what had been a system of neighborhood schools has become a marketplace. “Education functioning as a marketplace—that’s a whole capitalistic concept—perpetuates inequality and inequity.” She adds that those most disadvantaged by this educational marketplace are kids who are already disadvantaged to begin with, not those from families of privilege. As a mother and an educator, Andrews questioned why these kids are the educational guinea pigs in this experiment and not the white kids of privilege?

Andrews offered the “No Child Left Behind” policy as another example of “what the critical race theorist would say is an example of institutional racism.” This policy believed, she said, that if you just build accountability measures into the system, schools will

magically become better. As with the charter schools policy, Andrews presented data showing that not only was “No Child Left Behind” a failure, it exacerbated the problem by causing more black and brown students to drop out or be pushed out by the policy.

Another policy Andrews addresses as a critical race theorist is the inequality of tracking in schools. Tracking starts as early as kindergarten to influence a child’s academic abilities.

“Ability grouping does not have to be discriminatory,” she said, “if kids are able to move in and out of groups, but to often they get locked in. And most often, research shows, kids of color and kids living in poverty are in the lower level classes because teachers have lower expectations for their ability. Teachers have to check their bias at the door.”

These are three examples of institutional educational racism, said Andrews, as is the essentially Eurocentric curriculum that maintains a white supremacist master script, a script that a critical race theorist would call a revisionist history of a larger history.

“How you frame the issue helps you think about how you redress it,” Andrews concluded.

EVM Staff writer and reviewer Robert R. Thomas can be reached at captzero@sbcglobal.net.

You must be logged in to post a comment.