By Jan Worth-Nelson

This story has been modified from its original version to include further comment from Angela Warren, administrator of the Genesee Conservation District, and followup comments from CCNA president Mike Keeler — Ed.

When Mike Keeler, president of the College Cultural Neighborhood Association, noticed a seeming increase in tree cutting in the Seventh Ward area known for its silver maple canopies last summer, he got on his bike and started counting stumps. In a matter of two afternoons, he documented 180, many of which, he said, appeared to be all that was left of healthy trees.

Stump on Brookside Drive which has since been cored.

“So 180 stumps in a year — that’s a crime within itself,” Keeler said in a conversation with East Village Magazine. While some of the trees cut down were Norway maples, common replacements after elm blight of decades ago, and ash trees damaged by ash borers more recently, a number of the venerable maples also had been chopped down. While some stumps showed interior deterioration, others did not appear to be in bad shape.

Stump on Maxine Street clearly shows interior rot.

Alarmed, Keeler began a conversation with the Genesee Conservation District, the body responsible for tree removal decisions, about what is going on. His findings, along with escalating concern from homeowners in the leafy neighborhood, led to a visit to a recent meeting of the GCD board, followed by a special CCNA meeting last week where about 30 residents rallied to try to “stop the chainsaws,” as several of them put it.

In the meantime, the GCD, a contractor and partner with the city Department of Public Works and City Planning Department, is struggling to execute an urban forestry plan in a city whose priorities have been hugely overwhelmed by the lead-in-the-water crisis.

The role of the GCD requires some explanation. The Genesee Conservation District is neither a non-profit nor a for-profit organization, according to GCD administrator Angela Warren. Rather, it is an entity of state government — one of 78 such conservation districts in the state — making its relationship with the City of Flint a public-public collaborative partnership.

“We are in business to work with private and public landowners by applying best management practices to conserve and protect the state’s natural resources locally. Genesee Conservation District has served our community since 1946,” she said.

Perhaps it is not hard to understand how residents, having been beleaguered by undrinkable tap water and political betrayals going on three years, might find the loss of a beloved silver maple particularly galling, even if it was rotting at the core. Or that they would feel compelled to question official decision making.

But Warren and Jeffrey Johnson, senior conservation coordinator, see themselves as battling for city trees, too. They say they hope residents will understand that the recent removals in the CCNA are part of a city-wide strategy to assure a vibrant “urban forest,” as they call it, for the whole of Flint. It’s a legacy that they say they hope will live far into the future as the city attempts to reclaim itself from that other tragedy.

“We love trees, too,” said Warren, who herself lives in the College Cultural neighborhood. “We are passionate about this work.”

At issue are the “parkway trees” or “street trees” in the strip between the street and the sidewalk — property that is the responsibility of the city. Most of the silver maples in the College Cultural neighborhood were planted when the houses were built — many in the mid to late-1930s.

The life span of a silver maple is 75-80 years, meaning that most of the stately trees are in their dotage. In younger neighborhoods, elm trees were added to the mix, but in the Dutch Elm disease wave between 1950 and 1990, 77 percent of the nation’s elms were lost, including many in Flint. Norway maples tended to be planted instead. Ash trees were planted later, but many of them fell victim to a plague of ash borers.

Back then, the booming city had a robust forestry program which included publicly-funded tree replacements and maintenance programs, Keeler said. As recently as 2015, Flint was officially designated a “Tree City USA” for the 15th consecutive year by the Arbor Day Foundation, a title it still holds.

Warren said City of Flint officials have stated it’s a priority — part of the city’s latest Master Plan, in fact — to maintain the city’s urban canopy, and they have committed to making funds available for planting new trees.

The GCD is governed by a locally-elected five-member board. In a November, 2016 interview with EVM, Warren explained The GCD’s decisions about tree maintenance and removal are implemented by the City of Flint Street Maintenance department, and data about the trees is stored in the City of Flint Planning Department.

“We’re making decisions for the health of the urban forest, tree by tree, target by target. We have to look at every tree: is it contributing or is it a liability? As the work of arboriculture and municipal forestry grows, many lessons are being learned about the right tree for the right location. When these trees were planted, there wasn’t that knowledge,” Warren said. But at the same time, she said decisions have to be made around needs for the whole city, a challenge requiring much planning and expertise.

Another factor, she said, is that for a number of years, in times of scarce resources, the city’s trees missed out on needed attention. “We’re dealing with a problem that has been neglected, and we’re playing catch-up,” she said.

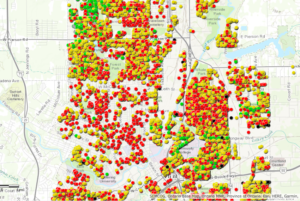

In early 2015, just as the city was shuddering under hints of the full-blown water crisis to come, the GCD released a grant-funded tree inventory produced by Knowles Municipal Forestry, an Ohio company run by forestry consultant Jason Knowles. He mapped every “street tree” in the city — a total of almost 30,000 — and categorized them as “good,” “fair,” “poor” or “dead.”‘ Every tree maintenance, removal, planting or pruning is documented in the resulting software program, which can be accessed at the City of Flint Planning Department website.

In followup to that mapping project and based on its data, Knowles produced an urban forestry plan for the city which the GCD is attempting to follow.

Of the 30,000 trees, about 2,000 were indicated as “critical removals” — constituting a liability and safety hazard — and another 4,000 tagged “immediate removals.” Another 12,000 were identified as needing “raises,” where overhanging branches are cut up from the bottom, and cleanings, which include pruning overgrown trees and removal of dead limbs.

So Mike Keeler’s impression that more trees were being cut down this year in the CCNA is accurate, Warren said. In implementing the urban forestry plan based on Knowles’ data, the GCD is rotating around the city. Last year they tackled tree needs in the north end, moving to the central city, and this year, to the CCNA and neighborhoods in the southern quadrants.

Winter canopy on Maxine Street (photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

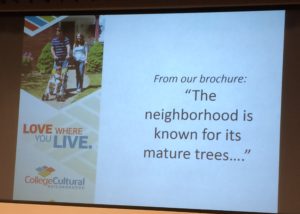

In a PowerPoint presentation to CCNA members, Keeler and his wife Sherry Hayden, vice-president of the CCNA, noted the neighborhood always has prided itself on its tree-lined streets. Trees are known to facilitate cleaner air, improved storm water management, energy savings, and increased property values and commercial activity among other benefits cited by the Arbor Day Foundation.

Residents acknowledged if a tree is diseased or dead it represents a safety hazard and should be dealt with. But they said they’re not convinced the decision-making criteria used by the GCD are being applied correctly, and in some cases are unclear and inconsistent.

Miniature look at part of the City of Flint’s “street tree” inventory. Green dots are good, yellow is fair, red is poor and black is dead. (flint.maps.arcgis.com

Tree-loving residents have been making use of Knowles’s data on the city website, but said they question some of the criteria — including the fact that there is not an “excellent” category for any city tree, skewing its decisions downward. In a PowerPoint slide, Sherry Hayden noted one tree given a “poor” designation and removed was to all accounts healthy, adding, “the tree only was guilty of being old.”

She accused the GCD of using an “illness model” that is biased against age.

“If they’re not dead, respect them,” she said.

The CCNA neighborhood touts its canopies as part of its charm.

The GCD’s budget is about $575,000, Warren stated, coming from sources including the City of Flint, Ruth Mott Foundation, and an anonymous donor through United Way of Genesee County. It also has received funds from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

In recent years, as resources have shrunk, the city has had to rely more on grants, outside funds and contractors. Tree replacements have been funded through private charities and donations, primarily from the Ruth Mott Foundation. But when the RMF changed its priorities last year partly as an outgrowth of the Flint water crisis, the tree replacement priorities also shifted.

CCNA residents say they want the emphasis to be on trimming, instead of removal. They suggest the GCD contractors make more money from cutting down the trees and thus may not be as motivated to assess the trees’ condition and maintain them by regular “raises” and clearing out dead branches. Keeler said he has learned contractors get paid $279 to trim a tree, but $750-$1,600 to cut it down. Keeler said in some cases judicious trimming could give even some of the silver maples 20 to 30 more years while replacement trees could have time to grow.

Warren disputes Keeler’s numbers. “The pricing quoted by Mr. Keeler is inaccurate,” she said. “The range for removal does not start at $750 (a tree can cost as little as $50-$100 to remove) and the range for trimming does not stop at $279 (a tree can cost up to or more than to $1000 to trim).”

In a follow-up phone call, Keeler said he had been given the numbers by a GCD board member.

The GCD’s Johnson acknowledged sometimes difficult decisions have to be made, and hoped homeowners would understand they are not made randomly. He said GCD staff use a “six-year rotation” in which they try to assess what it would cost to trim and prune an aging tree for six more years versus “taking care of business” by removing it now. He said it might cost up to $500 a year to maintain an old tree, for a total of $3,000 for six years, versus cutting it down for $750 to $1200.

Residents said they’d like more exploration of tree replacement protocols — acknowledging the need for both species and age diversity. Keeler noted “monocultures” of only one kind of tree can lead to mass die-offs if pests or blights come through; and age diversity means that not all trees run out their life cycle at the same time.

Keeler, who holds an Michigan State bachelor of science degree with a minor in wildlife biology and is a longtime Sierra Club activist, said in the interest of diversity he’d like to see the downed trees replaced with sycamores, horse chestnuts, hickories, lindens, basswoods, or hackberry trees.

He acknowledged not everybody agrees with his arboreal ardor. He said with a sigh that in his conversations with neighborhood homeowners, he discovered not everyone wants a replacement tree. “They don’t like having to get out the Roto-Rooter and they don’t like raking the leaves,” he said.

Warren agreed, noting much of their removal work is reactive, in response to residents’ requests — sometime in emergencies when an old tree dangerously keels over.

Residents have especially objected to what they said is inadequate communication from the GCD. In a follow-up phone call after the meeting, Keeler said the neighborhood association had received no outreach from the GCD about the urban forest plan or its implementation timeline.

“I don’t know what they thought we were supposed to think when 180 trees disappeared from our neighborhood,” Keeler stated. “If you’re only doing dollars and cents, where is the value of the community in the equation? That’s what’s wrong with this.”

One grievance voiced that the GCD contractors generally leave a door hanger, but residents noted it has contained no contact information for those wishing to appeal a tree removal or to ask for more information. Representatives from the CCNA plan to attend the 6 p.m. March 8 meeting of the GCD board at GCD headquarters, 1525 N. Elms Rd., and expect to issue a plea for more homeowner input into the process, among other requests.

Johnson said the door hangers have been revised to include the number. In addition, he said, homeowners will be invited to put their names on a waiting list for replacement trees. While the city’s budget is extremely limited, there still is enough, Warren said, to plant about 100 new trees a year.

In response to the residents’ complaints, Warren offered a more detailed description of the GCD process. “Using the inventory data to drive maintenance with contractors,” she said, “an inspection is made first at each tree by GCD forestry staff. During the inspection GCD leaves a door hanger to inform the resident at the address.

Further, she stated in a follow-up email, “All maintenance decisions are made by Genesee Conservation District. The contractor does not decide what maintenance is needed for any tree. The contractors are given a service request work order generated by GCD, after which they must provide a quote for the maintenance described in the work order. That quote is then analyzed and in some cases negotiated before approval. Once approved, the work on that particular tree can commence.”

“As an aside,” she said, “in a recent discussion with Knowles Municipal Forestry, we were told that GCD and the City of Flint’s process surpasses that of other communities by performing the inspection and leaving a courtesy door hanger. There are a number of checks and balances built into the process to ensure efficiency and satisfactory work is accomplished.”

“Over time, there is a plan,” she said. “It takes time.”

But she clearly bemoans the shortage of tree money. “If we had the funds, we would plant a new tree where every one has been removed,” she said. “If we had the funds, we’d plant trees in spaces where there isn’t even one now.”

CCNA homeowners were joined at last week’s meeting by their city council person, Monica Galloway, along with council members Kate Fields, Scott Kincaid and Council President Kerry Nelson. After hearing residents’ accounts of the disappearing trees, Nelson told the group they could count on council to review the tree cutting program.

“Definitely there is something wrong here with this program,” Nelson told the group after listening to their presentation. “The council needs to do something — to redo this program. I strongly believe that something needs to change.” He said he would advocate that the tree cutting program be put on hold pending city council review.

In the meantime, residents needing help with a downed or dangerous tree should call City of Flint Street Maintenance at (810)-766-7343, according to Warren. City of Flint officials can do some immediate tree removal, she said, while assessment for follow-up needs goes through the city to the GCD.

EVM editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.