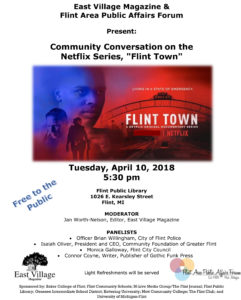

Ed Note: A community conversation about the eight-part Netflix series “Flint Town,” co-sponsored by East Village Magazine and the Flint Area Public Affairs Forum, is set for 5:30-7 p.m. Tuesday, April 10 at the Flint Public Library. Thanks to Ed Bradley for reviewing the series in advance of that event. The series, directed by Zackary Canepari and Drea Cooper, was released March 2. Flyer for the April 10 event reproduced below.

By Ed Bradley

Lew Morrissey, my first city editor at the Flint Journal, liked to encourage prospective writers and editors during job interviews to come to his city because it was a “great news town.” This may have been mere pragmatic praise, made to convince talented but skeptical journalists to take vocational chances on one of America’s most maligned cities – and this was in the late 1980s, pre-“Roger & Me.” But Lew was right – there always has been grist for the reportorial mill within our borders, if usually more for ill than good.

Zackary Canepari and Drea Cooper would agree on the “great” part. The longtime documentarians came to the Vehicle City to chronicle the rise of a little-known boxer, Claressa Shields, in her hometown gym. Their initial aim was to include Shields as just one in a group of aspiring Olympic Games athletes, but they took the kind of chance my old boss would have encouraged, as they narrowed their focus to the tough-punching teen nicknamed “T-Rex.” Their gamble paid off: In 2012, Shields won the first of her two Olympic medals, giving narrative and marketing boosts to Canepari and Cooper’s ensuing film, “T-Rex,” which garnered awards at multiple film festivals and acclaim from inspired viewers.

Zackary Canepari and Drea Cooper would agree on the “great” part. The longtime documentarians came to the Vehicle City to chronicle the rise of a little-known boxer, Claressa Shields, in her hometown gym. Their initial aim was to include Shields as just one in a group of aspiring Olympic Games athletes, but they took the kind of chance my old boss would have encouraged, as they narrowed their focus to the tough-punching teen nicknamed “T-Rex.” Their gamble paid off: In 2012, Shields won the first of her two Olympic medals, giving narrative and marketing boosts to Canepari and Cooper’s ensuing film, “T-Rex,” which garnered awards at multiple film festivals and acclaim from inspired viewers.

So how did Canepari and Cooper follow up “T-Rex”? Instead of being lured by brighter lights and fancier locales, they stayed in that “great news town.” Joined by co-director Jessica Dimmock, they followed the Flint Police Department closely for more than a year to make “Flint Town,” a revelatory eight-episode documentary for Netflix. Released in early March, the series is a compelling mix of “The Wire” and “Hill Street Blues” and a time capsule of the widening of the gap between two distinctly different Americas. It is eye-opening even to those of us who have lived in Genesee County for decades.

The problems central to “Flint Town,” which was filmed primarily in 2015 and 2016, seem almost implacable. With a force trimmed by budget cuts over the past 10 years from about 300 to less than100, the stressed-out FPD fears it cannot adequately defend a city populace (however diminished itself in number) of 100,000? With fewer police officers, the already-tense community feels disengaged from its protectors because it doesn’t see enough of them – or must wait too long for their arrival — on the street. The city government looks at diminishing budgets and unfavorable crime statistics and is reluctant or unable to devote more resources to public safety. The police perceive a lack of support from above, and the quandary comes full circle.

“Flint Town” unfolds during a crucial period locally and nationally, as the city’s water crisis attracts worldwide attention, shooting incidents involving police and public go on an uptick around the country, and the Trump-Clinton presidential election polarizes the nation (and the FPD). Moreover, the newly elected Flint mayor, Karen Weaver, replaces the incumbent police chief with Tim Johnson, whose efforts to restructure the department prompt a description as a “cowboy.” Johnson, who asserts that fighting crime is something he can “do in my sleep,” creates the C.A.T.T. Squad, a controversial unit targeted to high-crime areas (including the infamous Liquor Plus Mini-Mart on M.L. King), and seeks to fill the staffing void with volunteer citizen reservists.

Even if you know both outcomes, “Flint Town” builds real drama as the results of the U.S. presidential election and Flint public safety millage vote are decided on the same night.

But the real power of the series is in highlighting the grind of small-city police work and humanizing its practitioners, especially at a time in which they are under intense scrutiny.

Among those whose stories become relatable in “Flint Town” are Maria and Dion Reed, a mother and son who go through police academy training together; Lewis Spears, an upbeat senior citizen who eagerly vies for reserve duty because he loves his city; and Devon Bernritter, a captain who watches a routine traffic stop on the I-475 service drive become one of the series’ oddest incidents.

The officers worry not only about their community but also about their very job security; many of them have been laid off multiple times, and the pain of recalling those setbacks is palpable in their sit-down interviews with the filmmakers. Civilians get plenty of input in the series as well, in on-camera interviews and in candid moments, as when a concerned mother wonders that “you don’t know if you’re going to get a good cop or a bad cop” when one shows up on a 911 call. Some viewers may roll their eyes at the “ruin porn” of abandoned houses, but that won’t make any of the ruins go away.

The story-within-the-stories that gets the most attention is that of Bridgette Balasko and Robert Frost, two cohabitating officers whose personal goals may be at odds with a blissful future. Her dream envisions more than street patrol in Flint, Michigan, and he has family concerns that make him inclined to stay put.

One might leave “Flint Town” wanting more about, say, Brian Willingham, an officer who finds time from his law-enforcement duty to pastor multiple churches; he eloquently states his belief that “Flint will be bigger than any crisis.” But time and editorial decisions are always constraints in projects such as this.

Ed Bradley

“Flint Town” is no indictment of the police, or of the citizenry, or even of city government officials (although the last don’t come off as favorably). If it seems low on offering solutions, it is because the situation in Flint, and similar places, is fraught with uncertainty. “A new way to police,” as one officer states, may be at hand. So might a new way of solving problems in general. Whether there is more to come with “Flint Town” – and indications are that there will be – it deserves at least to spur constructive dialogue about crime, race and politics. Flint deserves to be known for more for its values than its poisoned water – and its hot-news takes.

Ed Bradley, a former longtime Flint Journal editor and writer, is the associate curator of film at the Flint Institute of Arts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.