By Jan Worth-Nelson

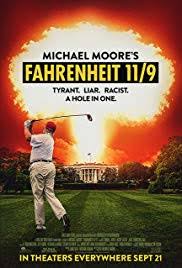

In his opening remarks to a crowd of about 1,000 at the screening of his new movie “Fahrenheit 11/9” Monday night at Whiting Auditorium in Flint, Michael Moore said he was trying to do his part to save the movies.

Movie theaters, he said, are “the last place that people can go to be with other people to feel, to laugh, to be angry, to be thoughtful.” His movies have often created just that sort of feisty audience solidarity. I was at the premiere of “Roger and Me” at Showcase Cinemas decades ago — in memory, now a comparatively innocent moment for Flintoids of almost adolescent anti-elitist hilarity. Most of us were in it together–even those of us who critiqued it. Later, when I saw “Fahrenheit 9/11,” it was again in a standing-room only theater– in L.A., that time — and I was startled when as the credits rolled, the crowd applauded and cheered–I felt touched and less alone.

Movie theaters, he said, are “the last place that people can go to be with other people to feel, to laugh, to be angry, to be thoughtful.” His movies have often created just that sort of feisty audience solidarity. I was at the premiere of “Roger and Me” at Showcase Cinemas decades ago — in memory, now a comparatively innocent moment for Flintoids of almost adolescent anti-elitist hilarity. Most of us were in it together–even those of us who critiqued it. Later, when I saw “Fahrenheit 9/11,” it was again in a standing-room only theater– in L.A., that time — and I was startled when as the credits rolled, the crowd applauded and cheered–I felt touched and less alone.

Before Monday night, the last time I saw Michael Moore in Flint was in the same place, Whiting Auditorium, on Nov. 7, 2016. I sat with my husband and a Clinton campaign worker who’d been staying at our house. We took exuberant selfies and then watched “Michael Moore in Trumpland” with the crowd of very blue-leaning Flintoids.

Even though Moore’s 2016 movie suggested the reality of the Trump voter, the state of a country divided and the desperation and anger of a whole huge chunk of America that had been left behind–including the victims of the water crisis in my own city–I thought things were about to turn around.

It felt like something momentous was about to happen.

I couldn’t wait until the next day when I’d vote for the first woman president, and then celebrate. My grandmother supposedly had been a suffragette; my mother was born ten years before women got the vote, and it felt like…finally…they both would get sweet vindication.

And of course, something momentous did happen.

As my husband and I shivered in horror in each other’s arms, clinging together at about 1 a.m. when Trump was declared the winner, I felt as if the country as I knew it had just cracked apart. I was so traumatized I literally couldn’t walk into our TV room for about three months–the taste of that defeat was too intense.

Later that night we poured whiskey for the Clinton campaign worker and her boss and stayed up until 4 a.m. in our bathrobes at the dining room table, in shock, trying to take stock.

Almost all my fears have come true.

And as Michael Moore says at the end of the new movie’s intro, even before the title comes up, “How the f–k did this happen?”

So walking back into Whiting Auditorium again, with Michael Moore up front about to screen his newest movie, a jeremiad and blast against Trump, I harked back to Nov. 7, 2016 and the day afterward. Even wearing my Andy Horowitz cap gamely exhorting “Make American not embarrassing again,” I felt less than sanguine.

In his opening, Moore said, “This could be our last film–because there is a process that has started to take our democracy away from us.”

Describing how he brought together a crew from many of his past projects, going all the way back to “Roger and Me,” he said he told them, “We have to make this film like this is the French resistance and the tanks are 20 miles outside of Flint.”

I do not want to be casual about PTSD, a real thing, a real terrible thing, but it feels as if the whole country has been in a nervous breakdown since 11/9. Unlike that 11/7 of two years ago, walking into Whiting Monday night I felt exhausted and not given to breezy expressions of hope.

Neither is Michael Moore.

Moore has always tipped onto the dark side, making us laugh as we slide into his selective horrors: nobody skewers and unmasks, better than Michael Moore, deliberately callous bureaucrats, conspiracies of domination by the oligarchs, suffocating violations of the common man and woman. This is part of the discomfort and seduction of his work.

Moore told the audience the past two years have changed him. In “Fahrenheit 11/9,” the darkness is front and center, un-ironic and catastrophic, and the laughter comes hard and bitter, if at all.

In combination with the run-up to the 2016 election, he delves into the shocked moments when that glass ceiling at Hillary’s victory party was NOT broken. He makes many comparisons of Trump to Hitler, substituting Trump’s voice over Hitler’s at a 1930s rally, the tone and stentorian chants unnervingly parallel. Not subtle. Two years ago I might have said, “oh, for cripe’s sake, don’t go overboard.” Now…the real threats of Trump’s authoritarian efforts are too close for comfort.

“It’s an awful thing to think that we might have elected the last president of the United States,” Moore said somberly. “He comes from the billionaire class of CEOs–they all hate democracy, they all hate that there’s one person one vote, because there’s a hell of a lot more of us than them,” he declared.

In developing his vintage thesis, Moore examines the Parkland shooting–including iPhone footage from students during the attack, and visiting the “war room” of the teens leading the charge for gun control in Florida. He ends the movie with the stunning silent elegy at the March for Our Lives in Washington last spring by Parkland survivor Emma Gonzalez.

And he spends a large chunk of the movie rehashing the water crisis in his hometown, the crucible of Michael Moore’s world view and the propelling energy of both his cinematic methods and his moral center.

We cannot again view the relentless history of the Flint water crisis, the crying children, the blind man getting water, the lies of state officials, the governor (booed in his appearance as he always is in Flint), the struggles to be heard–and find within any of it redeeming humor. Indeed, for the most part Moore doesn’t make jokes, except in his trademark “can you believe this b.s.” voice–he simply lays out, once again, the banal litany of corruptions and on the other end, the real-life tragedies, the broken trust, the wrenching disruption of a whole city still recovering.

As always, Moore gets a lot of things wrong–jumbling up timelines, overstating the worst, glossing over complexities, bending facts to a narrative of ridicule and maximum effect. It infuriates me when he gets the facts wrong, as when he called the Flint River, these days a shining example of gradual restoration, a “waste dump” and asserts that was what caused the water crisis, when in fact the story is more complicated. It was not the river. It was the lack of corrosion control and lead from the pipes, not the river, which created the havoc.

And of course, painting a portrait of recovery is not in Moore’s game plan. He repeatedly selects scenes most apt to elicit our “How could this happen in America” outrage. It was exhausting to see it all again.

Moore brings in the water crisis because, as he stated in his opening remarks to the Flint audience, “Governor Snyder was the coming attraction to what was coming to the rest of the U.S. You could have predicted everything about Trump if you paid any attention to what was happening to Flint.”

Standing up for the working class, as always, Moore asserted, about the Flint water crisis activists, most of whom were relatively uneducated and poor, “Nobody would listen to them.”

“STILL AIN’T,” I heard Flint activist Tony Palladeno shout from a front row. We are still enmeshed in it.

Moore’s passionate perspective on Flint’s significance to the nation produced one of the most memorable moments of the evening for me–again in his opening remarks. As it happened, the next day, Tuesday, marked the 1,600th day of the water crisis–since state and local officials switched the city’s water to the Flint River.

“That’s America,” Moore said. “This didn’t happen by accident, it was created like this…They [billionaires, corrupt politicians] know they can get away with it.

They did it, he said, to “this city, this city where organized labor got its start, this city that created the middle class… it started here. This city, which gave us our first black mayor in the country, this city that passed the first open housing law in the United States, this city.

“But you decided because of your greed, when you switched the whole city over to the river, once you figured out what the river was doing to people, you didn’t listen.”

Believe me, there is no one who wants to see Donald J. Trump’s chaotic administration end more than me. But the movie filled me with fear again and I went home anxious and depressed. I’m not sure what I wanted from “Fahrenheit 11/9” — not platitudes, certainly, not comfort. Maybe I wanted laughter again — the kind of shared, knowing laughter that makes us all think “we’re better than this and we’re going to throw the bastards out.”

That is, in fact, Moore’s central prescription. He powerfully makes the point that the real “winners” in 2016 were the 100 million people who didn’t vote, as Paul Rozycki pointed out in his September column here. Moore’s exhortation about what to do about our present predicament is reclaim our voice–to use our vote. As my husband said afterwards, “Voting is the only process we have for settling the disputes of our country nonviolently.” Moore forcefully argues the same.

So, while I walked out of there with my dread and horror exacerbated, like a scab pulled off, I’m thinking, maybe we will throw the bastards out, as my husband and my friends that night lustily predict.

But we’ll never be the same. We married that abusive husband and even if we get rid of him, it’s going to take a long time to fix the damage. Michael Moore, crying wolf, jester prophet of doom, has reminded us again that sometimes there really is a wolf in the henhouse. The worst really can happen. It takes us all, fighting back with Flinty resistance, to make it right.

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

The views expressed here are Jan Worth-Nelson’s personal perspective and not necessarily the editorial position of East Village Magazine as a whole.

You must be logged in to post a comment.