by Harold C. Ford

Get your name on 40 million cars and you’re bound to find fame and fortune. Nonetheless, David Dunbar Buick was forgotten first by the company that bears his name, then by the public, and ultimately by historians.

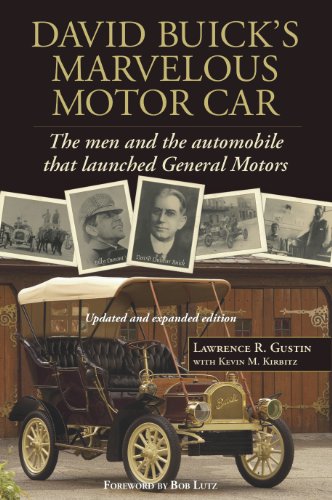

Author, Flint native, former Flint Journal reporter and retired Buick assistant public relations director Lawrence Gustin aims to correct this historical oversight with his 2006 book David Buick’s Marvelous Motor Car. A recently updated version includes mention of the water crisis, the virtual abandonment of Flint by General Motors (GM), and the resultant loss of 70,000 GM jobs.

Author, Flint native, former Flint Journal reporter and retired Buick assistant public relations director Lawrence Gustin aims to correct this historical oversight with his 2006 book David Buick’s Marvelous Motor Car. A recently updated version includes mention of the water crisis, the virtual abandonment of Flint by General Motors (GM), and the resultant loss of 70,000 GM jobs.

That ongoing history never fails to offer points of reflection. In light of the recent visit by some 700 members of the Society of Environmental Journalists (SEJ) to Flint for their 28th Annual Conference in Flint, Oct. 3-7, it seems appropriate to revisit Flint’s early automotive history through the lens of Gustin’s book.

After all, the site of the SEJ’s opening plenary session, titled “Future of Cars,” was Factory One on Water Street—the site of early Buick production and the Durant-Dort office building across the street is considered the birthplace of General Motors at the start of the last century. Factory One was one of the seminal sites for the last great transition of human transport, a century ago, from horse-drawn carriages to motorized vehicles. “Future of Cars” panelists envisioned this century’s transportation r/evolution to autonomous, electric, shared vehicles.

Flint pioneers:

Gustin’s book is chock full of the names of engineers, financiers, industrialists, and others whose names are indelibly etched in Flint thoroughfares, landmarks, and institutions: Dort; Bishop; Mott; Begole; Mason; Durant; Chevrolet; Kettering; Crapo; Whiting; Ballenger; Paterson; Stewart; Bower; DeWaters; and, of course, Buick.

And there are other names you should know for a more thorough understanding of this community that we live in that is a fount of great pride and considerable angst: Walter Marr; A.B.C. Hardy; Eugene Richard; Charles Annesley, and others.

Other well-known names in automotive history—Charles Nash, Walter Chrysler, and others—advanced their prominent careers during their time in Flint.

The reader is reminded that this great city began with a trading post established in 1819 by Jacob Smith; that it became a lumbering center, and a manufacturer of horse-drawn wagons; that it was visited by numerous dignitaries from Alexis deTocqueville (1831) to Teddy Roosevelt (1912); that it was incorporated in 1855; that it became the second largest automobile-producer in the world, second only to Detroit.

Without the contributions of these early pioneers, several of the important building blocks of Flint’s history would not have occurred including: formation of General Motors; creation of unique community/after-school programming; and the birth of the United Auto Workers which hastened the growth of America’s middle class.

Tinkerer, inventor, patent winner:

Gustin writes that Buick “displayed a talent for invention. Between 1881 and the first several years of the 20th century he was assigned 25 patents, mostly plumbing related…” Buick’s tinkering and inventiveness progressed from steam engines, to motorized tricycles and bicycles, to marine engines, to plumbing, then ultimately to the automobile engine.

The most important patent awarded Buick was for his valve-in-head or overhead valve design which significantly advanced the power and efficiency of the gasoline engine. Automotive writer Terry Dunham deemed it “the single most important mechanical factor in the early success of the Buick car.”

Gustin’s research and writing appropriately gives credit to Eugene Richard and Walter Marr for their contributions to the development of the overhead valve design. In fact, Gustin does a marvelous job of detailing how the inventions related to and development of the automobile can never be attributed to just a few individuals. In fact, Gustin’s book memorializes the collective efforts of dozens, hundreds, or more individuals who made creative contributions to the mass production of automobiles.

It becomes personal:

With Chapter Seven, “‘Valve-in-head’engines”, Gustin’s book became personal for me. My father, as is true for hundreds of thousands of others, would make his living and sustain his family from the earnings enabled by his labor and knowledge directly descended from the inventions of the early auto pioneers such as Buick.

The family on my father’s side was drawn to Flint in 1920 by the emerging auto industry and the resultant creation of jobs. My father left the auto factory’s monotony and became an auto mechanic. He understood the designs and machinations of the inventions by Buick and his contemporaries.

Consequently, my father put food on the family table and clothes on the backsides of his children with the money he earned. The link between David Dunbar Buick and Harold Richard Ford and Harold Clayton Ford is clear.

Ford, Buick, and others:

The automotive careers of Henry Ford and David Buick are remarkably similar. Gustin notes they were among the young men who would learn skills in Michigan during its “great industrial age that was beginning to muscle up”as the 1800s transitioned to the 1900s. It’s even possible that Ford, nine years the junior of Buick, may have been an apprentice under the direction of Buick at a machine shop in Detroit.

“The world was on the edge of a revolution in transportation,” Gustin writes. Michiganders Ford, Buick, and others were in close proximity during those formative years of the auto industry. Individually and collectively they created a synergy that launched the single most important and transformative land transport mechanism in human history—the automobile.

Gustin writes: “One historian has noted that in the early days, Flint had a group of men of unusual ability, many brought together by Durant, and ‘there was probably not a more lively bunch anywhere else in the country.’” It is worth noting that the sales of Buick automobiles often surpassed those of Ford.

Final thoughts:

David Buick died at age 74 on March 5, 1929, “leaving only his name on a car”according to one newspaper account.

Gustin tells us that not long after his death, Theodore MacManus and Norman Beasley in their book, Men, Money, and Motors, wrote: “Fame beckoned to David Buick—he sipped from the cup of greatness…and then spilled what it held.”

Gustin’s book is generously filled with visuals—vintage photos, newspaper clippings, documents, and maps—a total of 209 by this reviewer’s count.

Any individual imbued with the remotest interest in Flint’s history would be remiss if they skipped a read of Gustin’s book about Buick and his automobile.

[As detailed on his Amazon.com biography, Gustin has established his own venerable place in documenting and preserving Flint’s automotive history: “He authored three critically acclaimed and award-winning books: Billy Durant: Creator of General Motors, the first biography of Durant, in 1973 (with an updated edition published by the University of Michigan Press in GM’s centennial year, 2008); The Buick: A Complete History, co-authored with Terry B. Dunham in six editions, five updated (1980-2003); and the first edition of this book in 2006. He launched a newspaper campaign to save a building in Flint that today is a National Historical Landmark, considered virtually the birthplace of General Motors, and helped create the Buick Gallery and Research Center at the Sloan Museum.” In 2016 Gustin donated a major collection of General Motors memorabilia, included personal papers of Billy Durant, to the Sloan.]–Ed.

EVM Staff Writer Harold C. Ford can be reached at hcford1185@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.