By Harold C. Ford

“Journalism is the only profession explicitly protected by the U.S. Constitution, because journalists are supposed to be the check and balance on government. We’re supposed to be holding those in power accountable.” –Amy Goodman, Democracy Now!

A panel of veteran journalists tackled the existential issues that confront the nation’s fourth estate—journalism—at the Flint Public Library on March 26 before an audience of about 30. The panel discussion, “Have You Heard the News, Local News Sharing in an Age of Media Transition,” was sponsored by the Flint Area Public Affairs Forum.

Panelists included: John T. Counts, The Flint Journal news editor; Marjory Raymer, Flintside publisher and managing editor; Paul Rozycki, East Village Magazine political columnist; and Carma Lewis, Flint Neighborhoods United president. Serving as moderator for the affair was Dawn Jones, WJRT-TV ABC 12 news anchor.

Scary and exciting time:

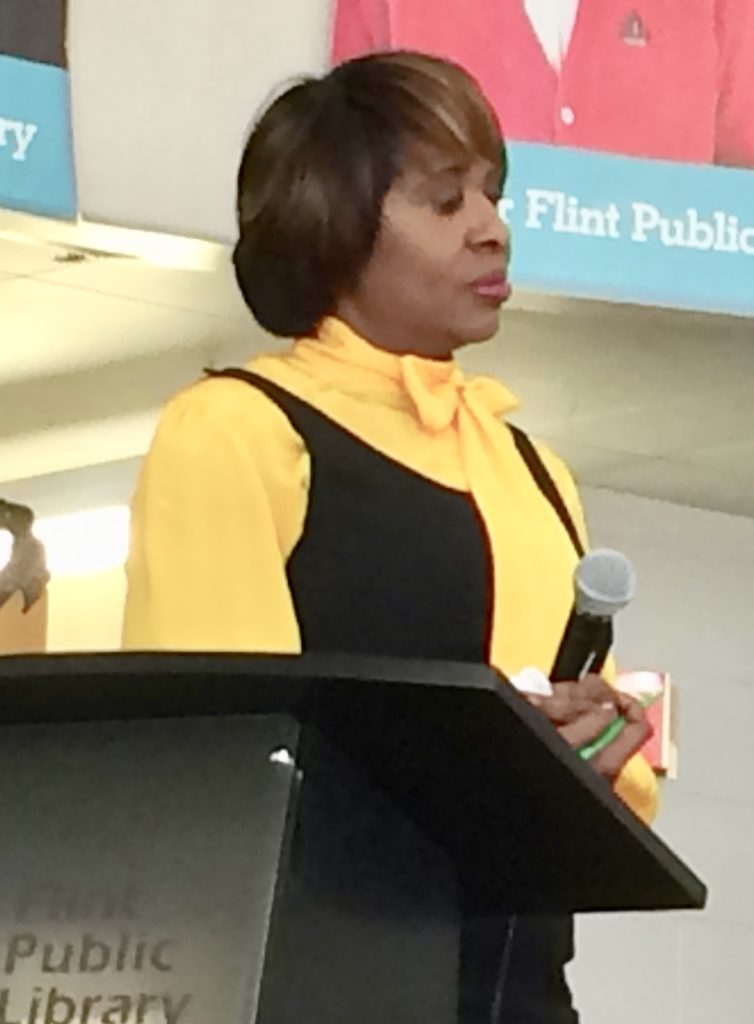

Moderator Dawn Jones (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

“It is a scary but also an exciting time to be a journalist in 2019,” Jones said in setting the tone for the 90-minute discussion. “There’s lot going on in this age of fake news (in) building the trust of your audience (with) the story you’re trying to tell, and (providing) the checks and balances” implied in the U.S. Constitution.

“Fake news” obviously referenced the drumbeat of verbal attacks on the press emanating from the nation’s Oval Office, while “scary” conjured images of recent attacks on the press, both real and conspired. In June 2018, five journalists were gunned down in a ‘targeted attack” at the Capital Gazette in Annapolis, MD. In October 2018, a Florida mail bomber included CNN, routinely condemned by Donald Trump, as one of his 100 targets.

First draft of history:

“Journalism is often called the first draft of history,” Rozycki said. “Sometimes the stuff we say is wrong, sometimes we change our minds later, sometimes we learn new information. But that first draft of history is the most important draft.”

Many historians would agree with Rozycki’s assertion. Joseph Baumgartner, in a piece titled “Newspapers as Historical Sources,” wrote: “The serious historian has always looked upon these (primary sources) as the indispensable material with which to construct a trustworthy picture of past events. In modern times, however, with the advent and proliferation of daily newspapers and weeklies, these have been increasingly utilized as sources.”

Community journalism:

“Community journalism is more critical now than it ever has been,” Rozycki said, “because of the fading of the old-line newspapers that were what we once relied on.”

Paul Rozycki (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

“In the age of easy publishing, there is an awful lot of community journalism of a very limited kind,” he said. “In one sense, every church bulletin is an example of community journalism.” The same is true for communications to and among hobby groups, charities, unions, colleges, and other groups, he added.

“The importance of community journalism is this,” Rozycki speculated, “in many ways journalism defines a community in ways we may not even imagine. We can define community in a lot of ways, geographically, politically…But another interesting way to define a community is to take a look at the news coverage people absorb.”

“When The Flint Journal had a lot bigger circulation, you could drive from Flint…and go to Frankenmuth, and you would mostly see Flint Journal newspaper tubes,” Rozycki recollected. “Somewhere along the way it started to shift; you would see Saginaw News. The mail boxes identified us in ways that we hadn’t been identified before.”

John Counts (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

“These communities are being created online,” Counts countered. “There’s all sorts of opportunities for people to get engaged.” He noted that the The Flint Journal’s parent company, New York-based Advanced Local Media with newspapers in about 25 cities, put together a national team of local reporters to specifically address the topic of gun control.

That gun control project began a month after the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting on Feb. 14, 2018 with 150 persons engaged in “strenuous dialogue” for 30 days on “closed Facebook.” Subsequently, 25 of those persons traveled to Washington D.C. for professional seminars on the topic of gun control. Reporters supported the freewheeling dialogue with fact-finding.

“That (dialogue) is something that journalism has always done and will continue to do with new opportunities through digital, through online forms,” surmised Counts. “There are new opportunities in this digital landscape.”

“The key thing is that community journalism has to be part of the community,” declared Rozycki. “They’ve really got to be so tied to it that they can speak truth to power when no one else will. This is especially true in Flint with all the distrust we’ve seen over the water crisis.”

“It’s not community journalism unless the individual is trained and understands what the responsibility and the role of journalism is,” Raymer warned.

Marjory Rayner (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Raymer described a “coming of age of myself” moment in 2009 when she realized “what was really, really important to me (was) community journalism. I have this inherent belief in my soul that journalism is a building block of community and democracy.”

“In order to truly function as a community we have to be able to have a certain level of communication and understanding of each other,” she said. “It’s important for me to know what’s happening in the block club. It’s important to me to know what the water coming out of my faucet looks like.”

Building trust in an era of “fake news”:

“The other issue we’ve got to deal with is the issue of fake news,” Rozycki charged. “Everybody can make news on Facebook. What’s true and what’s false and how do you sort all the stuff out?”

Carma Lewis (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

“Building trust is the key thing for any media outlet,” he said, “whether it’s a small community publication or whether it’s the New York Times. You’ve gotta build that trust. And editors are important; you gotta have a filter.”

“It’s easy to tell anything on social media,” cautioned Lewis, “so we still have to be very careful about what we put out there and what we take in. Just because it’s on the internet does not make it true.”

“Facebook, and Instagram, and all of those other social media sites give everyone a platform,” said Jones, “but as a consumer of the news you have to decipher what platform you’re going to believe…We have to decide who we’re holding accountable.”

“I think I get held way more accountable now,” answered Raymer. “It used to be you could hardly reach somebody. Nobody knew what I looked like, nobody knew anything about me back in the 1990s when I was doing journalism.”

Transition:

“I think tonight what we’re talking about is the community journalism that, in effect, replaces the mass journalism that is fading, the large newspapers that cover the whole community,” Rozycki said.

“In light of that, there’s been this rise of a whole range of publications to fill the gap,” he observed, “and the gap is caused by the decline of traditional journalism.”

Plentiful data supports Rozycki’s assertion of that “decline”. A 2017 Pew Research Center report found that overall newspaper circulation is down to its lowest levels in more than 50 years and that advertising revenue declined by 10% in one year from 2015 to 2016. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a 37% decline of reporters and editors in the 10 years from 2004 to 2014.

Rozycki cited examples of smaller Flint publications, past and present, that have filled the void of a diminished Flint Journal: Flint Voice; The Hub;Flintside;Flint Beat; Courier; My City Magazine; On the Town Magazine; Flint: Our Community Our Voice; and East Village Magazine.

The two main problems for smaller, alternative publications, according to Rozycki, are money and personnel. “Journalism is a labor-intensive work; it’s very hard to automate it. You need boots on the ground, you need a lot of reporters, and they cost money.”

Counts opted for a more optimistic approach about the “decline” of journalism by seeing “an opportunity to innovate.” He recognized the “nostalgia for old newspapers” growing up in a newspaper family, the son of a father who worked for the Bay City Times. He got into the newspaper business in the early 2000s when journalism began to be transformed by the digital age.

“There’s a new way of doing things,” he said. “There’s probably more information out there than ever before.”

Raymer remembered when the first computer arrived during her second job in journalism at the Traverse City Record-Eagle. She offered up the term “disruption theory” as a descriptor for the current transition of journalism. “I feel I’ve been living disruption theory for the last 10 years.” She became editor of The Flint Journal on March 23, 2009 when it stopped being a daily newspaper.

“An industry is going through tremendous, tremendous change,” asserted Raymer, “ and part of that is good. Social media availability for everyday people to have a platform and have their say is a beautiful, wonderful thing.”

“The disruption is how are we going to survive?” Raymer asked. “What is the long-term-sustainability for journalism? I do not believe that advertising is a long-term sustainable model for the news industry any more.”

Queries about staffing level at The Flint Journal rebuffed:

“There’s less local journalists,” Raymer lamented about the transition to digital.

“In terms of The Flint Journal…employees have been laid off in huge numbers,” said Rozycki. “There’s about 10 people or so in The Flint Journal today. As the numbers decrease, the workload increases.”

Counts was pressed about the current number of journalists at The Flint Journal by members of the audience including Jan Worth-Nelson, East Village Magazine editor.

Counts responded, “I’m not going to comment on that. I’m not going to comment on internal stuff.”

Former Journal writer and editor Michael Riha estimated that the staff level at The Flint Journal once numbered about 100 counting the editorial department, feature writers, editors, copy editors, sports writers, and feature writers.

Asked if reduced staffing leads to less effective investigative journalism which, in turn, leads to less well-informed editorial journalism, Counts replied, “That’s one disadvantage, sure. We still go out and hit the streets every day and investigate what we can.”

“This topic is not (just) about The Flint Journal,” chided Raymer, a former Journal employee. “This topic is about an entire industry. I get very protective of the journalists that we have working in this community because they work really, really hard.”

“People need to know a reliable place they can go, or places, where they can trust that they’re getting professional journalism, and it’s thorough, and it’s fair,” Riha said.

EVM staff writer Harold C. Ford can be reached at hcford1185@gmail.com.

Banner photo, from left: Paul Rozycki, John Counts, Carma Lewis, Marjory Rayner (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

You must be logged in to post a comment.