By Harold C. Ford

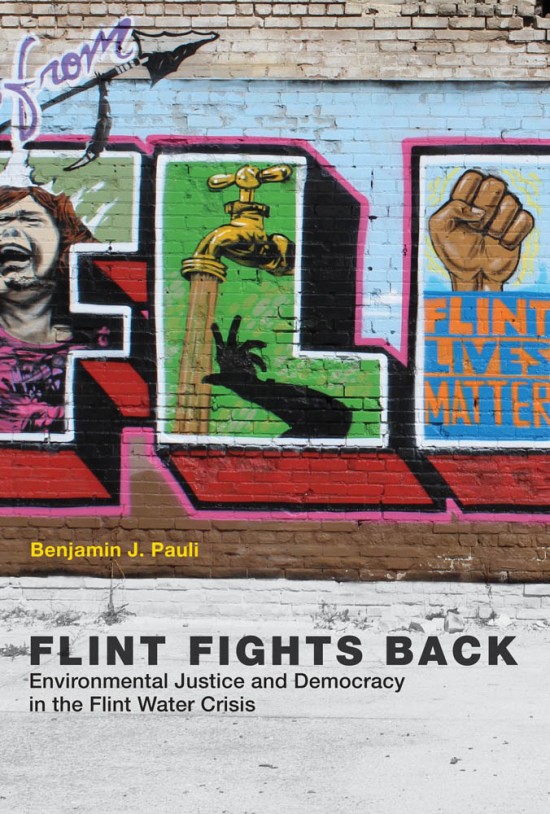

“The lesson learned from the battle over the river was that the hardheaded resolve of even a small group of people could move mountains.” … from Flint Fights Back, Environmental Justice and Democracy in the Flint Water Crisis,by Benjamin J. Pauli, The MIT Press, 2019

A wonderful photo is conspicuously positioned at the front of Benjamin Pauli’s new book on Flint’s water crisis, in which a water justice activist is holding a sign that reads “Poisoned Democracy, Poisoned Water, Justice 4 Flint.”

That sign could very well have been the title of Pauli’s new book Flint Fights Back: Environmental Justice and Democracy in the Flint Water Crisis.

In the 400-plus pages of Flint Fights Back, Pauli endeavors to draw a direct connection between Flint’s loss of self-rule with the imposition of democracy-sucking emergency managers (EMs) and the tragic contamination of its municipal water supply, certainly one of the most notorious man-made health crises in U.S. history.

In the 400-plus pages of Flint Fights Back, Pauli endeavors to draw a direct connection between Flint’s loss of self-rule with the imposition of democracy-sucking emergency managers (EMs) and the tragic contamination of its municipal water supply, certainly one of the most notorious man-made health crises in U.S. history.

Pauli, a social science professor at Kettering University who arrived in Flint in 2015 with his wife, a three-year-old son, and a new Rutgers PhD., investigates the politics and sociology of what happened with a compelling combination of personal and scholarly urgency.

The notoriety of Flint’s crisis likely had more to do with the trammeling of democratic norms than the befouling of water, the latter a consequence of the former, Pauli contends.

He writes that, “Reuters, which carried out the most extensive analysis, concluded not only that Flint was ‘no aberration’, but that ‘it doesn’t even rank among the most dangerous lead hotspots in America’ … Reuters found nearly three thousand areas with lead poisoning rates ‘at least double’ those in Flint during the peak of the water crisis.”

However, Pauli continues, “Nowhere — in the United States, at least — was the abrogation of democracy more literal or glaring. PA 4’s (Michigan’s EM law) affront to fundamental democratic values was so egregious … that it (was) used to catalyze popular resistance across lines of class, race, and geography.”

Poisoned by policy:

“The reason why the Flint water crisis was different from other crises,” Pauli, writes, “… why it deserved to be a state and national priority, was that Flint was not just poisoned, but poisoned by policy.” Pauli credits Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha for promulgating that concept when she testified before a panel of state legislators on March 29, 2016.

During the period of emergency managers imposed by the State of Michigan from 2002 to 2015, Flint’s water source was switched to the Flint River from Lake Huron, which had previously been provided from Detroit by the Great Lakes Water Authority.

Ben Pauli (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

As Pauli summarizes the debacle now so familiar to most Flint residents, “The switch introduced chaos into the water system” as Flint’s water infrastructure was ill-equipped to handle the more corrosive water from the Flint River. A host of illnesses and ailments that followed was believed to have been caused by the witches’ brew of contaminants in the water, especially lead.

“As old as Flint’s pipes were,” Pauli observes,“they were not so old that they would have crumbled in the presence of properly treated water … the crux of the technical narrative was a singular decision: the decision not to use optimized corrosion control during the water treatment process.”

“Most perplexingly opaque question”:

“Just who ‘actively pursued’ interim use of the river … is perhaps the most perplexingly opaque question in the entire water crisis saga,” Pauli writes. Though never definitive, the author points clearly to “the EM system.”

“The cost-averse logic on display in EM decisions about Flint’s water,” Pauli charges, “gave rise to the accusation that public health had been sacrificed on the altar of austerity, recklessly entrusted to glorified accountants whose powers were broad but whose expertise was thin or nonexistent on subjects central to residents’ well-being.”

Pauli observes that local water activists were less uncertain about where the blame lay: “Flint activists argued that regardless of whatever complicity EMs were able to elicit from local elites, it was the state — not the people of Flint or their elected representatives — that supplied the main political motive force during the period when the critical decisions were made about the city’s water.”

Canary in national infrastructure coal mine:

What also distinguishes Flint’s story from other similar health crises, is that its citizens helped to elevate the nation’s conversation about crumbling infrastructure.

“After Flint,” Pauli writes, some things changed. Significantly, [the] “pitiable condition of Flint’s water system offered an opportunity to talk about infrastructure on a national scale … cities around the country started proactively identifying and replacing their lead lines.”

Thus, it’s hardly a surprise that the $1 trillion infrastructure plan recently offered up by U.S. Senate Democrats, though stalled by Donald Trump, included $110 billion for aging water and sewer systems, the third most expensive item in the package.

Technical, historical, political:

The first half of Pauli’s book features three narratives of Flint’s water crisis: technical, historical, and political. The narratives are effectively augmented by 11 pages of timeline divided into two columns, one that focused on “water” events, the other on “democracy.”

He reaches one of several analytic high points during “The Historical Narrative of the Crisis.” His wisdom as an author is revealed when he draws from Andrew Highsmith’s 2015 book Demolition Means Progress for historical understanding.

“Flint’s toxic water crisis was fifty years in the making,” Highsmith wrote in an op-ed responding to the crisis in the Los Angeles Times. “As (Flint’s) population plateaued and then began to shrink …” Pauli recounts, “the city was left with an oversized infrastructure it could not afford to maintain.”

“Pulling all of these various threads together — industrialization and deindustrialization, suburbanization, segregation, the decline of government services, and ill-fated urban renewal — into a schematic of the prehistory of the water crisis yields a complex causal chain that extends all the way back to the early twentieth century and implicates a wide range of actors.”

Crisis in the context of democracy:

Pauli is not the first author to tackle the subject of Flint’s water crisis. Anna Clark’s The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy and Hanna-Attisha’s memoir What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance and Hope in an American City both have garnered waves of national attention. “There are already multiple accounts of what happened in Flint,” he concedes, “… and undoubtedly there are more to come.”

Pauli discussing “Flint Fights Back” at Totem Books last month — with participants Laura Mebert, Vickie Marx, Melissa Mays, Caleb Mays, Laura Sullivan, Tony Palladeno, and Jan Worth-Nelson (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

In the second half of his book, Pauli endeavors to examine Flint’s water crisis in the context of democratic struggles far away and nearby. More than anything, perhaps, this may distinguish Pauli’s treatment from others.

Michigan’s PA 4 took effect in March 2011 on the eve of the so-called Arab Spring, “a cascade of political rebellions that swept through the Arab world and beyond.” It was a time when Occupy Wall Street inspired a chain reaction of similar events throughout the U.S., including Flint. Wisconsin witnessed massive pro-labor rallies in response to anti-worker initiatives by that state’s governor.

In Flint, Pauli noted, “Everyone, it seemed, was talking not just about water, but about democracy.”

Crisis in the context of economics:

What may also distinguish Pauli’s book from others is his analysis of environmental justice issues, like those presented in Flint, in the context of capitalism. Borrowing from Eric Swyngedouw and Nikolas Heynen, Pauli acknowledges “the processes by which nature is ‘metabolized’ for human use under capitalism not only tolerate, but actually depend upon disparities of various kinds.”

Pauli echoes David Pellow when he warned against “reducing the complex social interactions that generate environmental injustices to dichotomous ‘perpetrator-victim’ narratives.”

Militant ethnography:

Pauli’s treatment of the water crisis was informed by his position within the water justice movement– another aspect of the book that sets it apart from the others. When he became a Flint resident in June 2015, with a three-year-old son, the water crisis became “first and foremost a deeply personal affair … we will never know if, during our use of unfiltered tap water … our son was lead poisoned.”

“I could no longer watch from the sidelines,” Pauli writes, as he evolved “from a fly on the wall into a full-fledged participant-observer.”

In April 2016, he was written into a grant from the State of Michigan to look into legionella contamination of the water supply, part of a team that became known as the Flint Area Community Health and Environmental Partnership (FACHEP) which also included Wayne State University’s Shawn McElmurry, the University of Michigan’s Nancy Love, and his Kettering colleague, Laura Sullivan.

A potential disadvantage, of course, is bias. Pauli admits that “… any narrative of the water crisis is an act of interpretation rather than neutral reportage.” An example might have been this assessment: “There was an aura around the activists … that I found alluring on both a personal and scholarly level.”

Conversely, an advantage was having insider information, a closer view. He draws “inspiration from Henry Kraus’s classic firsthand account of the Sit-Down Strike, The Many and the Few …”

Nowhere did this reader/reviewer find Pauli’s inside perch more useful than his detailed explanation of the sad falling out between water scientist Marc Edwards and other water justice activists. Time, energy, and resources were lost. Relationships were damaged beyond apparent repair. And it’s arguable that justice was delayed.

“While outsiders celebrated and even romanticized the water movement,” Pauli recognizes, “the view of the movement from the inside was far messier and more complex.”

Pauli also is distinguished in the book by his scholarly training as a social scientist, which both potentially enriches an understanding of the crisis and may challenge some readers, in sentences like “”But counterhegemonic narratives, too, incorporate strategic elisions and calculated points of emphasis.” The reader will have to become familiar with three of Pauli’s favorite e-words: ethnography; epistemic; epigenetic. The rewards are there both in terms of the context available and a deeper analysis of the activists’ movement than has been offered anywhere else.

Ambiguous ending:

“Four years after the first inklings of a water movement began to appear,” Pauli observes, “activists felt both that they had won extraordinary victories, and that, somehow, ‘nothing’ had changed and no solution to the city’s problems was in sight.”

Nonetheless, Pauli concludes that Flint’s water story is “what the democratic spirit looks like when imbued with the urgency of life itself.”

EVM Staff Writer Harold C. Ford can be reached at hcford1185@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.