By Robert R. Thomas

Flint author Connor Coyne’s Urbantasm is a serial novel composed of four books. Last year I read and reviewed Book One: The Dying City (EVM July 2, 2018). So surprised had I been by Coyne’s ambitious allegorical teen noir serial novel that I approached Book Two: The Empty Room with something akin to an elderly version of the unabashed exciting curiosity the Saturday matinee movie serials at the Roxy Theater brought my childhood.

Coyne, who returned to Flint in 2011 after years in New York and Chicago and is the founder and publisher of Gothic Funk Press, last year took Book One on a grueling coast-to-coast tour. Fortunately, in light of the gritty work of marketing his opus, the book has garnered national recognition.

Urbantasm, Book One: The Dying City won the 2019 Next Generation Indie Award for Young New Adult Fiction and is a 2019 Semifinalist for the Kindle Book Awards for Young Adult Fiction. It also was selected for the New School’s 2019 Alumni Summer Reading List–Coyne’s master of fine arts alma mater–all encouraging Coyne to continue with his heartfelt saga of a teenager struggling to grow up in a city based on Flint.

So, what’s next for the novel’s narrator, John Bridge, and his colorful crew? What’s next for Akawe, their rusting hometown, the dying city of Book One? What happened after Drake and his crew, high on O-Sugar, jumped off the roof of the abandoned St. Christopher hospital [remember St. Joe’s]?

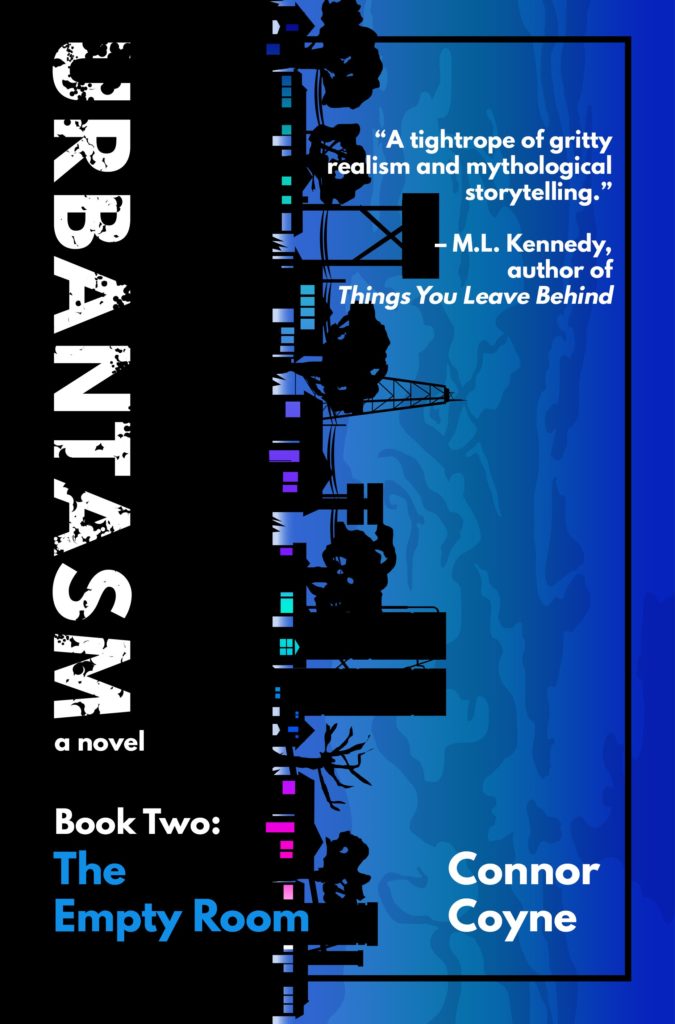

Book design by Sam Perkins-Harbin/Forge 22 Design

The noir nature of Coyne’s impressionism of Akawe is imbued with fictionalized Flint-specific references viewed through the eyes and experience of 13-year-old John Bridge and his teen comrades in post-industrial urban survival. In the first two books long, spooky night walks through Akawe are awakening experiences. Childhood innocence dies as adulthood comes aborning in a world gone wrong—often, horribly wrong.

Instead of looking through rose-colored glasses at contrary realities, a mysterious pair of blue sunglasses John lifted from a homeless man continues to stalk Coyne’s allegory as a totem for viewing horrible realities.

The second book opens with a prequel to John at four years old having just been spanked for climbing onto the roof to escape his baby-sitter and scaring his parents.

“Why is there so much blue? I wondered. Back in my bedroom, lying on my stomach on my bed, my head turned to the side, I saw the naked maple branches waving outside my window. ‘You saw what happened,’ I told the tree. ‘Please don’t tell anyone.’ The branches nodded.”

The blue bottle glasses and the listening whispering maple roll on into Book Two like a faithful call-and-response chorus witnessing to the tale and its realities. Here John focuses his quest in growing up succinctly: “I want to be real.” To that end, of course, there are fiery tests. So it goes in the land of life and death that is fictional Akawe as well as its rust-belted model, Flint.

Another long pondering night walk through Akawe finds John at the home of his old and the first of his female friends with whom he had made out. Selby is suffering from scarlet fever and John is suffering from anomie. He climbs through her bedroom window at her invitation. They smoke pot. For John it is the first time. Their conversation—a further awakening to new life and broadening horizons—includes Selby Demenescu explaining “urbantasm” to John.

“Do you ever think,” said Selby. “I mean, have you ever seen something that was destroyed? Like destroyed and gone? And you see it right in front of you? Like it still exists? Only it’s blue or purple. And you can see right through it.”

Selby recalled a Romanian character from her childhood, Manole..

“telling us kids about it. He said he saw them all the time in Cartierul (a neighborhood in Akawe). More than anywhere else he had ever been. He called them urbantasms. Urbantasmele. Because he saw them in the city. In Cartierul, where the city has pretty much disappeared, and it’s all muddy and swampy. He saw urbantasms here. He saw the whole living city all around him. It scared him.”

“Why would it scare him? You just told me yourself that they couldn’t do anything.”

“Even just seeing something does do something. I mean if you see something– if you sense it–then you’ll know that it’s there. That it exists. And if you think of what it is in any choice you make after that. You know? But… but also, it means that the past isn’t completely gone. Like the past can catch up with the present, you know? Like the past lives with us in the present? And then we all go into the future together? So I guess he felt, like the urbantasm, and that he could see them, it meant that past and present and future weren’t really different. Like they were all with him all the time. The past tries to run away from us. But he discovered you could run up behind it and catch it. And also, the urbantasms told him that Akawe was a true city. He said he couldn’t see them in most cities, but he could see them here, and that made a difference.”

“What do you mean? What is a true city?”

“I mean, any city is just a place where there are all a lot of people living this whatever– their lives–all together. Right? So a true city with urbantasms would be like, everyone is altogether, and all time is altogether, and everyone is part of one big thing, altogether, and that big thing is the city. Is Akawe.”

I knew, I felt, exactly what she meant.

“Anyway,” she said,” That’s another thing that the blue sunglasses made me think of. Like I wonder: if you see urbantasms, and you don’t want to, and you put on blue sunglasses… does that mean you can’t see the urbantasms anymore?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “in some ways, you know, this shit is all so weird… I don’t even know how it could all fit together. But because it’s also weird, I kind of don’t know how it couldn’t. You know?”

“Yeah. I know. That’s it. Exactly.”

It is conversations like this that enliven and broaden perspectives—both of the characters and the reader. Dialogue is a major tool in Coyne’s prosody for delineating characters and propelling his allegory. The characters are authentic because their voices and their concerns are authentic. At no point in the first two books did my readerliness feel I was being talked down to by the author or the narrator.

Connor Coyne (photo by Eric Dutro)

As for the cliff-hanging ending to Book Two, I offer only this teaser: the kid in me who watched those movie serials was not disappointed. I can’t wait for Book Three, which I plan to read right here in my garden where I read Book Two beneath five grand old maple trees listening and whispering above me.

Coyne and his wife Jessica live in Flint with their two daughters, Mary and Ruby. He is cofounder of the Flint Festival of Writers (formerly the Flint Literary Festival) and teaches writing for teens at the Flint Public Library.

Urbantasm, Book Two: The Empty Room will be published Sept. 28, and can be ordered from Totem Books or other independent bookstores or through online distributors including Amazon and BarnesandNoble.com.

EVM Board Member and frequent book reviewer Robert R. Thomas can be reached at capnz13prod@gmail.com. EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson contributed to this report. She can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.