By Harold C. Ford

“In the signing of the 1819 treaty by the Chippewa and Ottawa, (Jacob Smith) had earned himself several hundreds of dollars in payment from the government for his secret work, while also quietly sowing the seeds for his white children to each receive hundreds of acres of desirable property where white settlement would almost certainly take place and a town (Flint) would grow.” …from The Daring Trader, Jacob Smith in the Michigan Territory, 1802-1825, by Kim Crawford.

Two-hundred years ago, a U.S. delegation led by Lewis Cass, Michigan territorial governor, met with leaders of the Michigan Chippewa and Ottawa tribes at the site of present-day Saginaw to negotiate a treaty. A staggering 4.3 million acres of land were gained by the U.S. including parcels along the Flint River that would become the city of Flint.

From Sept. 17, 1819 to Sept. 24, 1819—nearly 18 years before Michigan achieved statehood—a U.S. team of negotiators secured land that would become 12 Michigan counties, more than half of eight more counties, and parts of nine other counties. In return, their native counterparts won an annual payment of $1,000, the services of a blacksmith, cattle, farming equipment, and teachers to show them the white men’s ways of agriculture.

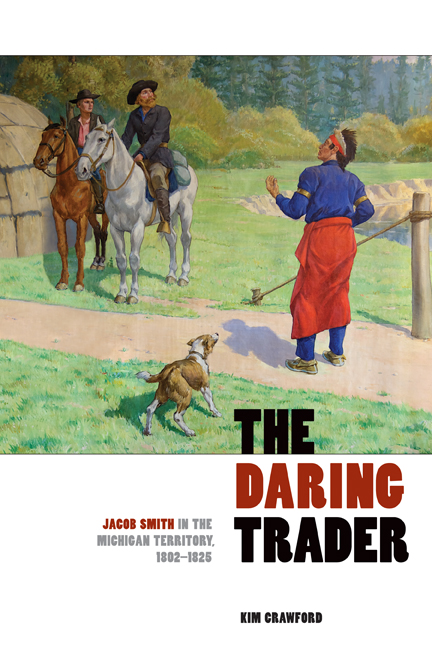

(Cover image from MSU Press)

The impact of these talks on the history of Michigan, including Flint, was profound. And playing a critical role at the 1819 council was Jacob Smith, a fur trader that author Kim Crawford dubbed the “founder of Flint.”

Crawford discussed Smith’s role during an event earlier this year at Totem Books. His 2012 book, The Daring Trader, Jacob Smith in the Michigan Territory, 1802-1825, is available at Michigan State University Press.

Smith’s role in the 1819 Saginaw council

The War of 1812 between the United States and Britain had concluded by 1815 with the Treaty of Ghent. Nonetheless, hostilities between the former rivals, including Britain’s Indian allies, continued, especially along the frontier in what had been the Northwest Territory including Michigan. Detroit and southeast Michigan were especially vulnerable due to its frontier position on the Great Lakes. The 1819 treaty council in Saginaw was intended to resolve the ongoing tensions between the U.S. and Indian tribes.

Smith’s role in the treaty negotiations is open to several different interpretations:

“On one hand, he was acting as a secret agent on behalf of (Territorial Governor) Cass to get the Chippewa and Ottawa to approve the cession of a huge portion of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. At the same time, he was also laying the groundwork for his children to claim and eventually receive thousands of acres of land by getting Indian names for them into the treaty.”

Somehow Smith acquired plots of land for his five white children and another half-Chippewa daughter, Mokitchenoqua whose English name was Nancy. Many suspected fraud. “The law was a white guy cannot be granted land in a treaty,” Crawford told the Totem Books audience of some 15 persons. “Smith clearly manipulates events in Saginaw.”

Jacob Smith historical marker in Carriage Town (flickr photo by Michigan Municipal League/mml.org)

Smith had assigned Indian names to his five white children. Harriet Garland became Messawwakut at the treaty talks; Louisa Payne, Annokitoqua; Maria Stockton, Nondashemau; Caroline Smith, Sagosequa; and Albert Smith, Metawanene.

“Smith saw opportunity on the Saginaw Trail at the Grand Traverse of the Flint River,” Crawford said. “He was also carefully stage-managing events…Whoever gets control of that land is going to succeed in a big way.”

Neome, leader of the Flint River band of Chippewa who was friendly with Smith, may have helped with the acquisition of land for Smith’s children. “(Smith’s) son-in-law, John Garland later claimed the friendship between the fur trader and Neome was real and true,” Crawford writes. “And that was the reason Neome had wanted Smith’s children to have land on the Flint River.”

Daring Trader brings Jacob Smith to life

Many Flint area residents know Jacob Smith as the first white settler of the land that would become Flint, but little more. Crawford, former long-time police reporter and feature writer for The Flint Journal, remedies that with his meticulously researched 305-page book that includes nearly 50 pages of notes and bibliography.

“You’re going to look long and hard to find a more complete account of the treaty (and the man) than what I’ve done,” Crawford told his Totem audience.

Smith was “first and foremost a fur trader,” Crawford writes. At various times in his life, he was also a market butcher, storeowner/businessman, and father. He served Michigan’s first two territorial governors as translator, soldier, courier, and confidential agent.

Smith was constantly in the courts. “It is possible that he enjoyed these legal battles given his propensity for getting into them,” Crawford said.

A Canadian by birth, “(Smith) risked his life and fortune on behalf of his adopted country (the U.S.) during the War of 1812.” He was arrested and thrown into a prison in Montreal. Changing roles, he posed as a British agent in order to travel into “Indian country” where he was more comfortable than his contemporaries.

“By long residence among the Indians he (Smith) had assimilated his habits and ways of living to that of the natives, even to the adoption of their modes of dress,” Crawford writes. “He spoke their language fluently and correctly…The Chippewa gave Smith an Indian name: they called him Wabesins (Young Swan).”

Adventure and danger were commonplace for Smith. Crawford correctly suggests that episodes in Smith’s life are the “stuff of a James Fenimore Cooper novel.” Nothing may illustrate this more than Smith’s rescue of the three children of Nicholas Boyer who had been captured by the Chippewa.

“At a time when Indians were still killing and abducting white settlers around Detroit,” writes Crawford, “it was no small risk for an American to loiter unguarded at the edge of town, let alone leave it and ride into the Saginaw Indian country.”

Yet, that’s just what Smith did. He “took a couple of pack horses, loaded with goods,” wrote historian Benjamin Witherell, “through the wilderness to Saginaw, redeemed the children and brought them in to their mother.”

The heroic and successful rescue of the Boyer children inspired Charles P. Avery, a mid- nineteenth century lawyer and amateur Michigan historian, to dub Smith “the daring trader.” Thus, the title for Crawford’s book.

Detroit and Flint

Smith was a resident of Detroit before he settled along the Flint River. He established homes there, started a family, grew a business, and interacted substantially with many of Detroit’s early and most prominent citizens.

Daring Trader deepens the historical appreciation of readers through its inclusion of persons and places familiar to readers as present-day monuments, buildings, landmarks, and streets that dot the landscape of southeast Michigan, including:

Lewis Cass; Solomon Sibley; Louis Campau; Stanley Griswold; Father Gabriel Richard; Elijah Brush; Augustus Woodward; James Witherell; Alexander Macomb; Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac; Jonathan Kearsley; Fort Shelby; the Wyandot tribe; the Saginaw Trail; the Grand Traverse; river La Pierre (Lapeer); the village of Copeniconic (now Camp Copneconic); Chief Grand Blanc; and Pewaunaukee (“place of fire stones” or “flinty place”) which would, of course, become Flint.

Land ownership after the treaty

Disputes endured over who owned the land along the Flint River. On Jan. 22, 1835, Indian leaders affixed their totems and Xs to a document acknowledging that the Flint River reservation(s) belonged to the Smith children. Nonetheless, legal battles over the land would continue until 1860.

The husbands of Nancy’s white half-sisters bought out her interest in the section of land that was set aside for her.

Land along the Grand Traverse was divided and subdivided; ownership passed from one generation to the next. “There are literally thousands of deeds in Flint, Michigan that will go back to the (11 square miles) of the Smith Reservation,” Crawford said.

Smith’s final years

Census data from 1820 indicates that “Smith was farming near his Flint River trading post.” Smith’s dwelling was a small log house about 90 feet from the bank of the river. It stood on a clearing of several acres that had been fenced.

“Evidence is clear,” Crawford writes, “that Smith was falling on hard times by the early 1820s. Smith died a poor man in 1825 at age 52. Avery would later claim that Smith died “from neglect as much as from disease.”

Smith was buried in “a rude coffin” at a “secluded spot near the (trading) post,” according to one account in a Saginaw County history. It is likely that his trusty and reliable friend Neome was there.

“In less than a few years, a small community of French-Indian families would exist here… followed by white Americans from the east in the 1830s,” Crawford writes. “The town would be known as the Flint River Settlement at first, and then Flint.”

Reviewer’s note: Kim Crawford told his Totem Books audience that a Native American friend and attorney advised him it was appropriate to use the term “Indian” in The Daring Trader. This review reflects that advice.

Banner: Part of the book’s cover image — the painting is an artist’s depiction of Jacob Smith and his friend Neome. It hangs on the third floor of the Genesee County Courthouse.

EVM staff writer Harold C. Ford can be reached at hcford1185@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.