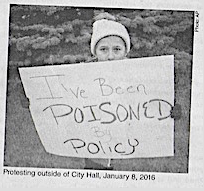

News photo reproduced in Nickel’s Flint book

By Robert Thomas

An abiding iconic Flint visual for me is the news photo of a child holding a protest sign stating the case for what happened in Flint: “I’ve been POISONED by Policy.” The photo quickly leads to the question: “How does that happen?”

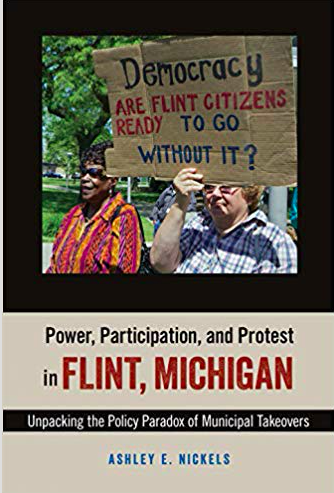

Ashley E. Nickels, a professor of political science at Kent State University, offers cogent insights in her book Power, Participation, and Protest in FLINT, MICHIGAN. The subtitle, Unpacking the Policy Paradox of Municipal Takeovers, reminded me of that child’s sign. I thought about how a public poisoning is very real while policy is all theoretical—until it becomes a reality.

“The municipal takeover policy shows a preference for technical rationality, eschewing politics,” states Nickels. “But a municipal takeover not only fails to avoid politics, it also creates new politics.”

Her book is a scholarly, accessible analysis of the “policy paradox” of municipal takeovers “wherein political struggles over conflicting values are often obscured by a discourse of rational decision making, short-term fiscal stability is pitted against local democracy, and neoliberal market solutions are valued over democratic principles of participation and deliberation.”

As Nickels demonstrates, “there are inherent conflicts in municipal takeover policy: it pits the values of the “market”—rationality, efficiency, and technocratic managerialism—against the values of the “polis”—equality, equity, and participatory democracy.

Moreover, the debate over municipal takeover, about both its design and implementation, illustrates these important value conflicts and the paradoxes that underlie the policy’s ostensible rationality.”

Using policy as her analytical lens and Flint, Michigan, as the investigative site for her case research, the author blends contextual research, interviews, and analytical tools into the book’s narrative. The book’s analysis of the framing of Flint’s poisoning-by-policy is telling in terms of both theory and practice.

Framing is an analytical tool used to define a problem, identify its causes, pass judgment on what might have caused the problem, and offer solutions.

“For example,” Nickels writes, “proponents of municipal takeover focus on budgets, efficiency, and numbers, whereas opponents focus on democracy, rights, and accountability.”

To understand framing one must understand the context in which it exists. In this case, the context is Flint and its state takeover twice by four emergency managers. Recalling the Flint takeovers in 2002 and 2011, Nickels examines the allocation of resource benefits and burdens.

In other words, who benefits and who pays the price under emergency management rule?

Chapter 5, “The ‘Development Agenda’— Implementing Municipal Takeover in Flint,” highlights what happened when a policy (development) set an agenda and implemented it via emergency management theories and practices.

As the author notes in the book’s Introduction, “policy scholars have a tendency to view ‘policy’ as rational, systematic, and scientific, while eschewing ‘politics’ as ‘an unfortunate obstacle…to good policy.’ Yet, in the case of municipal takeover, attempts to depoliticize management are inherently political and have important political implications.”

As the author notes in the book’s Introduction, “policy scholars have a tendency to view ‘policy’ as rational, systematic, and scientific, while eschewing ‘politics’ as ‘an unfortunate obstacle…to good policy.’ Yet, in the case of municipal takeover, attempts to depoliticize management are inherently political and have important political implications.”

Chapter 6, “From Development Agenda to Development Regime — Allocating Benefits and Burdens and Interpreting Winners and Losers,” examines which stakeholders benefited from emergency management and which stakeholders were disenfranchised.

“While the development regime gained access, a disproportionate resource burden was placed on low-income and Black residents,” writes Nickels. “These disparate policy burdens had both instrumental (e.g., resource) and symbolic (e.g., interpretive) effects.” Here the author identifies “the disparate allocation of resource benefits, resource burdens, and participatory access,” while outlining “how different constituent groups made meaning out of the policy, focusing primarily on their interpretation of winners and losers.”

Chapter 7, “Defending Democracy,” shifts the framing of top-down stakeholder interests to bottom-up, disenfranchised grassroots interests. The contrast between these two groups is evident in the framing of their policy differences. Nickels summarizes:

The grassroots associations used intersectional frames that served to identify differences among community members, while simultaneously identifying the power and privilege that underpin the systemic oppression of Flint’s people. The activists drew on narratives of past exploitation and collective power in their framing of the problem. In this way, they both identified how local power structures shaped their individual experiences as well as ways in which those shared experiences provided a platform for solidarity.

“On the other hand,” Nickels continues, “the development regime, comprising mostly HCNPs [high-capacity nonprofits] created a narrative of equal suffering for all residents of Flint. This adherence to lay colorblind, and class blind, strategy was in direct opposition to the grass roots associations. Here the development regime was not explicitly telling racial stories, but their focus on the past is the past and the natural and unfortunate causes of the water crisis ran parallel to this narrative. Moreover, their lack of discussion about structural oppression and their emphasis on equality further scaffolded the color blind racism of the development regime.”

Grassroots Flint activist Claire McClinton frames policy in terms of democracy versus fascism:

In their zeal to transfer the Flint water system to bondholders and other corporate interests—a Michigan city was poisoned. We have to publicize and shine the light of day on the fascist offensive going on in Michigan…. The backdrop is that Flint is the home of GM, and also the home of the great sit-down strike that established collective bargaining with GM. Flint was a game changer within the labor movement and the acceleration of unionization nationwide…. [W]e have become a throwaway disposable class where people’s lives don’t matter anymore.

What the development regime does not say in their framing is anything about guilt or complicity or criminal culpability.

“In Flint,” according to Nickels, “development-focused nonprofits were careful to not assign blame to any particular entity when discussing the crisis, focusing on mitigating the effects of the water crisis in a reactive way. In general, these organizations focused little attention on what might have caused the crisis in the first place, nor on the topic of criminality.” Her basis for this conclusion is the analysis of 72 documents issued by HCNPs in response to Flint’s poisoning by state theory and practice. Only 5 of those 72 documents mentions anything about the status of democracy in Flint. Much of the thrust in their framing, according to the author’s analysis of their own documents has to do with moving forward with technical solutions

Another key element the book exposes regarding technical and governmental solutions to the crisis is related to democratic issues such as the normative value of popular sovereignty that emphasizes local control and representative democracy. Related to the issue of local control is the issue of transparency and accountability, especially when it comes to setting policy and an agenda for implementing it.

“Democracy is messy, yes,” concludes Nickels. “But decreasing access to local decision makers increases distrust among residents and provides openings for local elites to control or shape the agenda. Putting measures in place to ameliorate this problem would go a long way toward diminishing the lack of access to local power. In other words, deliberation and inclusion are essential to making laws aimed at addressing fiscal crises more socially equitable.”

This is the book’s central focus: Is fiscal stability to be pursued at the expense of social equity?

For the gentle reader whose concerns with this book might invite crossed eyes and theoretical bafflement, I confess to similar feelings when I approached Nickels’ scholarly treatise on the theory and practice of policy, specifically unpacking the policy paradox of municipal takeovers.

But the beauty of reading a book is how it might surprise one. This book surprised me with its blend of scholarship, i.e., research and development, and its composition. The author’s narrative is a compact accessible blend of investigative research and reporting backed by details delineated via charts, appendices, and copious notes and references—all of which I found helpful and enlightening as the backstory of the narrative.

Robert Thomas

I also found the book’s scholarship refreshing in an age when an official spokesman for the leader of the free world declares that “the truth is not truth.” Nickels speaks truth to that bad baloney, which is exactly what true scholarship should do.

EVM Board member and reviewer Robert Thomas can be reached at capnz13prod@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.