By Jan Worth-Nelson

I didn’t want to write this. I didn’t want to think about it. It was awful, and there was nothing good about it that I can think of. And with the state of the nation the worst of my lifetime and in my view bound to get worse, reflecting on the Kent State shootings, 50 years ago today, seems only an exercise in lacerating disillusionment in the compounding failures of my country. I wish it was more hopeful, but this is my truth of today.

I guess I come to this because I was there.

The notion of witness, the responsibility of witness, goads me as it has all through the decades since four students were killed by bullets of the National Guard and nine more were injured — one paralyzed for life — on a hillside of an otherwise unremarkable Midwestern campus– a public university of no particular prestige — on a mild May day. You can read all about it many places today; Harold Ford’s book review posted here, for example, summarizes the details.

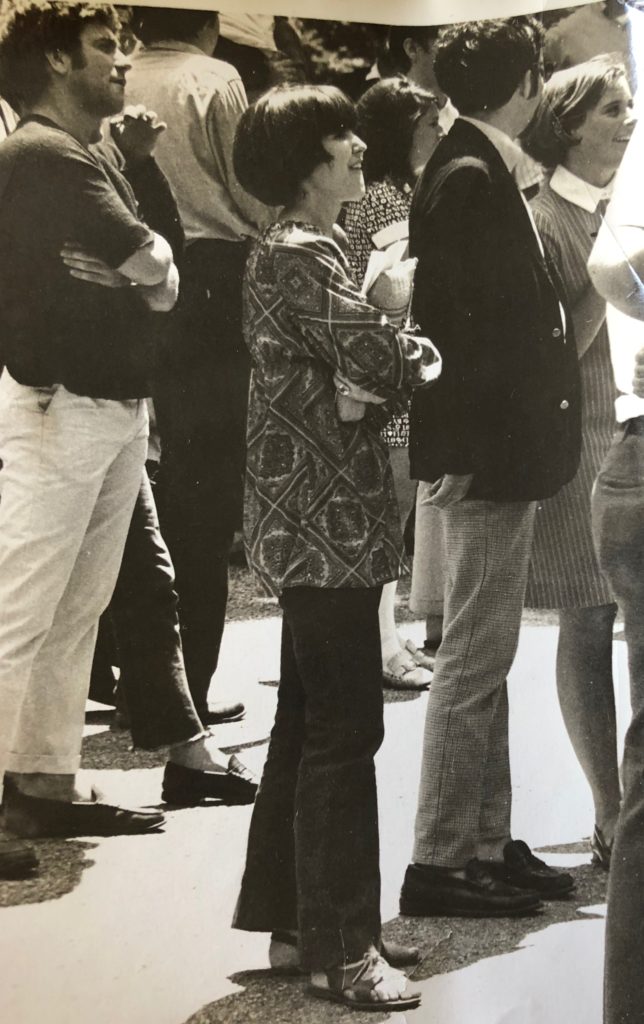

Worth-Nelson at a protest in Ohio, 1969.

I was a 20-year-old journalism student stretching my wings, almost unmanageably eager to be part of “the world”– to experience everything I could. My background autobiography is tiresome to me now, tedious to repeat: I was a preacher’s kid from Canton, Ohio living in an attic apartment across from campus–my relationship with my parents a cliche of rebellion against the smothering pieties of an evangelical world.

So…I joined the weekend protests, our fury rising after Nixon announced an invasion of Cambodia. I sat on the hillside Saturday night, fragrant pot smoke wafting, as somebody set fire to the ROTC building, a set of quonset huts. The watching crowds crowed, laughed, cheered. I was impressed by the audacity of it, but also uneasy. I left. Monday I dutifully went to class–a big political science lecture class — as tanks stood guard on every intersection. In the middle of class, wails of sirens burst out and our professor, pale, ended class and told us all to go home. I’ll never forget the eerie next moment: outside the building, a short walk from Taylor Hall, everybody stood there almost silently, in shock, afraid to move. “They’re shooting people…” was the horrified murmur moving through us like a tremor. I walked toward it. Blood was everywhere. Screaming, confusion. The bodies gone.

My dad, now dead for 30 years, came and got me, fighting his way through the barricades at the entrance to town. “My daughter’s in there,” he said he shouted. Whatever was going wrong between us got a little bit of healing that night. We sat at the kitchen table together, his rage something I would never have imagined. “It could have been you,” he said, as I cried. “There is no excuse for what they did.”

I have been back to Kent State only once in the entire 50 years. My first husband wanted to see it. We went onto campus and made the appropriate tourist stop, the bullet holes preserved in a metal sculpture. I felt sick to my stomach and experienced a quavering bout of misery. We quickly left and I’ve never been back.

Another memory and another place comes to me now. About 35 years after Kent State, I visited Washington, D.C. for the first time. By then, I had wrestled my way into and painfully out of that flummoxing first marriage, and blinking into the sunlight of a second one, wanted to see at last the nation’s capitol.

Things had not turned out so much the way I thought they would in life, but my second husband and I had met in the Peace Corps, and we knew it was because of that one wonderful adventure–when we served our country, without guns, and felt good about it — that we were starting over, this time in grownup love, determined to do it right.

Veteran posting before the Vietnam War Memorial (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

We went to the Peace Corps headquarters and the driver we’d hired took a picture of us kissing there–a photo I have sadly lost. We went to the Vietnam Memorial and allowed our hearts to hurt again in that epic place inviting us to grieve for the nation’s sins and for the 55,000 Americans lost, all so young — part of the Kent State story.

People looking up at the Second Inaugural, Lincoln Memorial (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Most of all, we went to the Lincoln Memorial, where, standing in front of the wall of the Second Inaugural, reading those breathtakingly beautiful words, I allowed myself to believe in America. D.C. is about ideas–ideas manifested in architecture, partly–in all that piled up marble that makes it seem we are not only strong but capable of thoughtful elegance. You see it everywhere you turn in D.C.: reminders of the American Dream we understand was always a flawed promise, dreamy in concept but infuriatingly problematic in execution. But it felt good, at least for a weekend, to savor those ideals, however shredded by reality.

That moment has been steadily assaulted by hard truths, hard life, hard politics, hard ignorance, so many deaths, so much violation of whatever good we aim to live by.

Let me put it this way: in 1970, I thought the other world — the one outside what I experienced as Protestant banalities — was better. I thought that’s where I wanted to be, where I should be, where it would be exhilarating to be.

Even after JFK was assassinated, even after Malcolm X and Martin Luther King and RFK, I nurtured a Woodstock notion of the world.

“We are stardust, we are golden,” Joni Mitchell assured us in her lyrics for Woodstock, that haunting anthem for the Sixties. It’s like an elegy, now, listening to it — knowing what was to come. But back then I felt it, my heart full and hampered by almost no doubt: We were stardust, we were golden.

And maybe we were, for a time. But Kent State cut a huge, brutal slash into our exuberance. It cut our spirits down. The worst message of all, since proven over and again in a hundred different ways, right up to the water crisis in the town that has been my home for 40 years, is this: the government can kill us, and does — sometimes by design.

Brothers and sisters, there’s no denying it: things have gone deeply awry, and maybe it takes Mother Earth, finally, to bring us up short with this virus to stop the whole shebang: to stop our depraved misuses of the earth and our delusional pursuits of–of what? Sometimes I can’t even figure out what that is. But here I am, 70 years old and in the 50th day of sheltering in place in quarantine, as we head toward 70,000 dead, and the Kent State observances, planned for years, were cancelled, and the worst president in my lifetime is attacking another one for his loving call to unity.

My heart is broken — for what happened then, and for what is happening now. Sometimes life does not deliver redemption. Maybe that’s the one thing I’ve learned in my 50 years since those young Americans were cut down by soldiers from their own country on a bloodied Ohio hillside on a sunny, springtime Monday in May.

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com. The views represented here are Worth-Nelson’s alone and do not officially represent the views of East Village Magazine as a whole or its governing board.

You must be logged in to post a comment.