“It doesn’t look good when you’re divided … it makes you look dysfunctional.”

–Shaquana Davis-Smith, treasurer, Pontiac Board of Education

“We’re not going to present a united front as if everything is OK, because it’s not OK.”

–Laura MacIntyre, treasurer, Flint Board of Education

By Harold Ford

At a special meeting of the Flint Board of Education (FBOE) Nov. 16, five Pontiac School District (PSD) officials shared their remarkable story of financial recovery with FBOE members. In the past decade, PSD turned a $52 million debt into a $7.9 million surplus.

A slide presentation titled “Best Practices: Lessons Learned, Steps Taken to Financial Solvency” stimulated conversation in the two and a half hour meeting not just about the importance of data-driven fiscal strategies but also eventually about effective partnerships and how to engender trust.

(Graphic source: Flint Community Schools)

At the start of the last decade, PSD officials found themselves in an existential predicament very similar to that confronting FBOE members at present: financial instability; declining student enrollment; a low rate of high school graduation; multidirectional mistrust; and pressure from the State of Michigan to make things better.

Resolving to make improvements, PSD officials undertook affirmative steps that yielded measurable progress:

- In the past decade, PSD turned a crushing $52 million debt into, at present, a $7.9 million fund surplus – the first time in 20 years PSD has reported a positive fund balance.

- A $147 million bond proposal was passed by Pontiac voters in March 2020 on a third attempt after board members, school officials, and others went into the neighborhoods on a weekly basis to drum up support.

- PSD has welcomed and cultivated relationships with more than 50 community partners.

- Pontiac High School has raised its graduation rate from 59 per cent in 2014 to 76 per cent in 2019.

- The district’s curriculum has been reshaped to include preparation for careers that do not require a four-year college degree. One wing of a PSD school building puts students on a “pathway” to skilled occupations such as nursing.

- PSD was released from its consent agreement with the state, a status currently existing between the state and FCS.

- Most important, perhaps, is the progress PSD made on trust issues in all directions.

PSD officials at the Nov. 16 meeting included: Kelley Williams, Pontiac’s superintendent for the past nine years; Gill Garrett, board of education president; Kenyada Bowman, board vice president; Shaquana Davis-Smith, board treasurer; and William Carrington, trustee, a product of Flint schools.

FBOE members present included: Carol McIntosh, president; Joyce Ellis-McNeal, secretary; Laura MacIntyre, treasurer; Adrian Walker, assistant secretary/treasurer; and trustees Chris Del Morone and Allen Gilbert.

Danielle Green, board vice president, was absent. Kevelin Jones, interim superintendent, sat in the audience. (Jones was appointed superintendent of Flint Community Schools (FCS) at the FBOE’s regular meeting the next night.)

Jessica Thomas, administrator of the Michigan Department of Treasury, began the meeting by explaining, “Our goal is to analyze the fiscal health of school districts across the state … and (provide) technical support, tools, resources, and data.” After few comments, Thomas yielded the remainder of the time for the PSD presentation and subsequent discussion.

Muddled financial picture

FCS is under pressure from state government, specifically the Department of Treasury, to achieve financial solvency. At least two amended Enhanced Deficit Elimination Plans (EDEPs) were sent to Treasury from the district in calendar year 2020.

EDEPs seek to achieve balanced annual budgets and eliminate long-standing debt.

FCS has been burdened with substantial debt for nearly a decade, largely the result of an approximate $20 million loan taken out by the district in 2014. Declining student population and resultant loss of state aid have also contributed to the district’s challenging financial picture.

(Photo source: Flint Community Schools)

As reported by East Village Magazine in June 2020, Carrie Sekelsky, former FCS executive director of finance. projected a fund balance deficit at the end of fiscal years 2020 and 2021 of nearly $13 million.

Much has happened in the past two calendar years to muddy the financial picture of FCS:

- Flint voters approved a fiscal stability bond proposal in March 2020 allowing the district to restructure 4 mills for the purpose of more quickly paying off the district’s debt.

- FCS student enrollment has declined to about 3,000 students signaling a commensurate declination in state aid.

- The state aid formula, based on student enrollment, was recently increased to a baseline per-student amount of $8,700.

- The new Michigan school budget includes $135 million to districts, like Flint, with a year-round or “balanced calendar.” The new budget also includes “new teacher” stipends of up to $1,500; FCS has plenty of new teachers and is looking to hire more.

- FCS expects an infusion of cash in three waves from the Federal Government in the form of ESSER (Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief) or COVID-19 Relief funds.

- Special education programs in Flint and neighboring school districts will receive about $9 million as a result of lawsuit settlements related to the Flint water crisis.

- FCS officials have likely come to the realization that abandoned school buildings – most requiring millions of dollars in upgrades – are not likely to be a “goldmine” for the district, as once predicted by board treasurer MacIntyre.

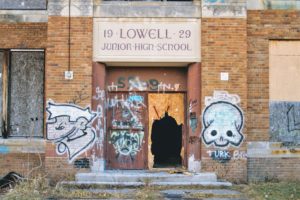

Lowell Jr High school was in operation as a school from 1929 until 1988. From 1988 to 2012 it was used as an alternative education facility. The school is now shuttered. (Photo by Tom Travis)

- Infrastructure challenges in old buildings that currently house FCS students continue to drain money from the FCS budget. Hot buildings served by outdated HVAC (heating, ventilation air conditioning) systems closed schools for several days in August. Black mold remediation is underway at Doyle/Ryder and bat removal at Potter.

- An offer by the Flint-based C.S. Mott Foundation to help renovate or rebuild FCS school buildings may only be in the beginning discussion phase.

FCS’s financial picture is muddled such that it brought back Sekelsky on a part-time basis to help clarify the district’s financial state. Prior to her departure from FCS in November 2020, Sekelsky led an in-house effort that made progress toward fiscal clarity, according to a report by the auditing firm Plante Moran.

Treasury Department report is not muddled

A report by the Michigan Department of Treasury was very clear about FCS finances as of Sept 1, 2020. It showed an audited fiscal year 2019 fund balance of -$3,349,028.

Flint was one of 10 districts in the state listed as “Current EDEP Districts.”

The Treasury report included the following statement:

“ … School District of the City of Flint is projecting a positive general fund balance for FY2019-20 due to a fiscal stability bond and additional ESSER funding, however, the District projects to remain in deficit until FY2035-36.”

Sharing stories

“We are here to share our stories,” said PSD’s Williams. “This is a partnership.”

Gill, a former police officer, said he was young and naïve and resisted input from Michigan government about a decade ago.

“Who gonna tell me about Pontiac?” recollected Gill rhetorically. “I’ve been in Pontiac all my life!”

“Well, ‘all your life’ ain’t saving these students,” Gill eventually concluded.

Trust

Trust was a theme throughout the meeting. Pontiac officials said trust was a scarce commodity at the start of their EDEP process.

“We did not trust Treasury initially … the Michigan Department of Education, and we did not trust our ISD (Oakland County Intermediate School District), Williams admitted. “Our guards were up.”

(Graphic source: PSD Facebook page)

Trust issues extended to and through and among PSD administrators, teachers, support staff, and district partners, recollected Williams. “It was not easy getting all of them to the table because there were trust issues.”

Gaining trust from the larger community was particularly daunting, Williams recalled. “Building that trust is not an overnight process … We had to show them we were going to be good shepherds.”

Williams and other members of the PSD team said they built trust through “courageous conversations” and “build(ing) relationships” at community meetings held on a weekly basis for five years. “It took all of us to do this.”

Communication

PSD officials declared that poor communication, in all directions, also handicapped their school district at the start of the EDEP process.

There existed in 2012, “a lack of effective communication among the board and administration,” Williams recalled. “Some board members knew what was going on and some did not … information was held in silo(s).”

“It is a board of eight (counting the superintendent),” Carrington said. He warned of consequences “if the school board does not have an effective communication with the superintendent.”

“If your board is not communicating with the superintendent, it will not work,” Garrett agreed. “I needed to learn how to communicate from the top all the way down to the bottom.”

Those comments by PSD officials prompted Flint board president McIntosh to admit, “My board, they don’t trust nobody, not even me.”

Student-centered, data-driven

Williams urged “prioritization of student achievement” as a guiding principle for FCS officials. “What can be resolved is how you’re going to educate your children.”

Williams said PSD educators committed to the notion, “All Pontiac students will significantly increase scores on standardized achievement tests.” Toward that end, pillars were built around academics, attendance, and student/building climate.

Carrington admitted that safety was the number one issue that drove students to transfer to charter schools.

Williams said PSD educators focused on both non-academic and academic needs of students. “You want to find programs that (distinguish) you from other surrounding districts.” Toward that end, PSD revamped the wing of one of its buildings to provide curricula for careers that do not require a four-year degree.

Dual enrollment in college and high school classes was initiated.

PSD officials minimized their differences and pooled their energies to gain passage of a $147 million bond proposal to, in part, address the infrastructure needs of the district.

“Buildings were terrible,” Williams admitted. “The students didn’t really have a positive environment for learning,” Carrington added.

“Zen spaces” were created that addressed “the whole child,” Bowman said.

“The goal of the board of education is to make sure that we produce a product (such) that our kids … have an opportunity to live a life that they so choose,” asserted Garrett,

Williams emphasized that the district is guided by “data-driven decisions.”

Partners

Williams said PSD committed to enlist partners “that would help us get to where we (needed) to be.” She declared, “We would not have been able to make it without our partners because we did not have the money.”

Varied partnerships included Amazon, General Motors, the State of Michigan, Oakland Schools ISD, a local auto dealership, and others.

“They (partners) came in and wanted to help in the areas we needed help in,” recalled Williams. “They were soldiers.”

Parting comments

“You’re in such a beautiful position,” Williams said. “The storm has cleared away a lot of things and all you have to do is come up with a plan. Get that EDEP done. Get those ESSER dollars spent.”

“Use this as an opportunity to help change your culture,” Garrett advised, “to help guide who you are. We’re not getting this moment back.”

Echoing the words of a former president, Garrett concluded: “Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change we seek.”

EVM Education reporter Harold Ford can be reached at hcford1185@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.