By Paul Rozycki

A therapist trying to analyze Flint’s attitude towards race might use the term bipolar.

On one hand, Flint was the first major city to choose an African-American mayor, Floyd McCree. It passed one of the first open housing ordinances in the late 1960s, after a community sleep-in at City Hall. A Republican governor came to support the effort. It’s been the home of the United Auto Workers (UAW), historically one of the more progressive unions in the nation. In contrast to many cities, Flint avoided major conflicts during the Black Lives Matter movement, when the county sheriff responded to a request from civil rights activists to “walk with us” during the summer marches in Flint and Genesee County.

I-475 corridor downtown Flint. (Photo by Tom Travis)

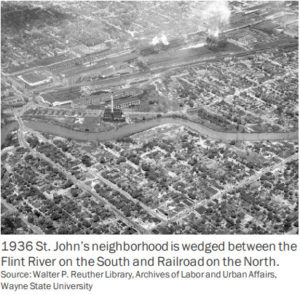

Yet, on the other hand, Flint has been categorized as one of the most segregated cities in the nation. In the early and mid-twentieth century, homes built for GM workers by the Modern Housing Corporation included restrictive covenants prohibiting sales to any but white residents. Many city parks were assumed to be open to whites only. Banks and finance companies commonly ‘redlined’ parts of the city to limit mortgages in minority areas. Entertainment at the old IMA, in downtown Flint, had a program for whites early in the evening, and one for Blacks around midnight. Today, the Flint City Council can rarely get through a meeting without some racial bickering between council members. Before the 1970s, Black residents were generally limited to living in two areas of the city—the St. John Street area in the north, and Floral Park to the south.

The I-475 freeway

That racial divisions in Flint and Genesee County have been revealed in a thousand ways over the years, but one of the most visible has been the creation of the I-475 expressway, that runs through the city, just east of downtown. Built in the early 1970s, it runs from the Grand Blanc area in the south, through the city of Flint, and joins I-75 well north of the city, in the Beecher area.

Aerial view photograph of I-475’s path through Flint. (Photo by Paul Rozycki; Photo source: MDOT)

Building I-475

Plans to run an expressway through the city of Flint began in the early 1960s, as General Motors and others sought to connect several GM plants, and divert the industrial traffic from city streets. While there were several options available, the final plans took the new highway through a major Black neighborhood, the St. John Street area.

While some considered the area to be in need of urban renewal, the freeway became a means of removal. In spite of any problems that existed in the St. John neighborhood, such as industrial pollution, some have labeled it “the Black Wall Street” for Flint. Because of discrimination elsewhere in Flint, the St. John Street neighborhood was where most African-Americans did their shopping, visited restaurants, and sought entertainment. In his book “Demolition Means Progress” Andrew Highsmith wrote that the I-475 project ultimately increased Black poverty and segregation. He said that the rate of Black home ownership fell from 50 percent to 15 percent after the highway was built.

Floral Park neighborhood. (Photo source: MDOT)

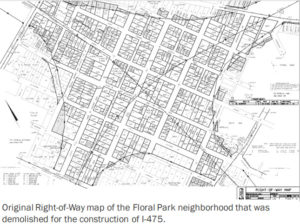

There were several reasons for choosing the St. John Street route, all linked to race. From an economic point of view, a low income neighborhood was a less costly path than clearing out a more upscale area. Taxes were low, as were property values. From a political point of view, the push back from a minority neighborhood was likely to be less intense than from another middle class area. The reaction from residents of the Central Park area, west of Central High School, was one reason the expressway wasn’t placed there.

The promise of urban renewal

When the I-475 highway was first proposed, in a 1963 report from the Michigan State Highway Department, titled “Freeways for Flint,” it was promised as an urban renewal project for the St. John Street community. Those promises, and the advent of open housing laws, led many residents to initially support the idea, according to Andrew Highsmith. However, the implementation of the highway project, and urban renewal, led to a dramatically different outcome.

MDOT public information meeting held at The Whiting on March 22, 2022. (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

The I-475 project was delayed by federal budget cuts and rising costs of the Vietnam War in the mid-1960s. But since everyone knew that the St. John Street area was soon to be taken for the expressway, all but routine maintenance was deferred, and home values declined. During this time, the Flint City Council passed an ordinance prohibiting anything but the most essential repairs and improvements to property in the area. As a result, residents’ property was purchased at low prices, and those forced out often lacked the funds to find good housing elsewhere.

The expectations of racial integration were also dashed. While Flint passed an open housing law that prevented formal segregation, when the residents did find new housing it was often in neighborhoods that were still informally segregated, or in public housing within the City of Flint, rather than in the suburbs. With some variation, the Floral Park community to the south, faced similar challenges.

Members of the public viewing large maps at a MDOT public information meeting at The Whiting on March 22, 2022. (Photo by Paul Rozycki)

A 2017 report issued by the Michigan Civil Rights Commission titled, “The Flint Water Crisis: Systemic Racism through the Lens of Flint” came to the following conclusion about the impact of the I-475 project on Flint’s Black community:

“In the end urban renewal caused more harm than good. Flint’s vibrant African American communities had been razed, the good along with the deteriorated and overcrowded. The existing urban culture was erased. In its place are freeways, a theme park, and other underused facilities that, like Flint’s water system, were built for people and businesses who largely are no longer there.”

Flint’s experience was not unusual. Many cities, as they built freeways and tollways, often found that, under the banner of urban renewal, it was easier to put the concrete pathways in low income, minority communities. It was economically cheaper, and it was politically less contentious.

The highways got built, but the promised urban renewal never quite happened. Often the relocation of residents led to continued segregation rather than integration. Often that relocation destroyed the personal connections that developed among neighbors. And all too often, the new highways separated racial communities, and made it easier for white residents to move out of the city, and commute from the suburbs.

What’s next for I-475?

In light of all the history of I-475, the State of Michigan is developing plans to rework Flint’s urban highway. The Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) is planning a $300 million project that will redesign I-475 from Bristol Road to Carpenter Road. The project could began in the spring of 2024 and could free up as much as 30 acres of land for development downtown. Today as the future of the highway is being reconsidered, residents are being asked to offer their views on its future.

It has held public meetings, and invited comments from the public in the hope that the errors of the past won’t be repeated. A meeting on Tuesday, March 22 at The Whiting presented the proposals, and heard comments from the public about the future of the highway in Flint and Genesee County.

At the well-attended meeting, several major proposals were presented, including four options for the future of I-475.

The first was to do nothing, leave the highway as it is.

The second, was a modest modification of the existing freeway, with four lanes and some updates.

The third option was a reduced footprint freeway, cutting it back to four lanes, with other modifications.

And the fourth option was to create an urban boulevard in the downtown, with connections to the urban grid.

During the question and answer period, several who lived in the area raised questions about the noise level of the freeway. Others supported the idea of a bike path and provisions for walkers in the downtown. Several hoped that whatever plan was finally adopted would be successfully maintained in the future. Some raised the issue of the impact of the freeway on their neighborhoods.

In addition to the public meeting, comments from the public can be submitted by mail, an online comment form, e-mail, or phone.

As reported in Tom Travis’ EVM story of March 8, the meeting at The Whiting is available on line at bit.ly/I475OnlineMeeting until April 4. Public feedback to MDOT can be also be given through email at MDOT-I475@Michigan.gov or by calling (517) 335-4381. Mailed comments should be directed to Monica Monsma, MDOT Environmental Services Section, 425 West Ottawa St., P.O. Box 30050, Lansing, Mi. 48909.

Whatever the final design of the highway, boulevard, or parkway, the real question is “Will this be a road that leads to racial reconciliation in Flint?”

To help answer that question, be sure to make your voice heard.

EVM political commentator and columnist Paul Rozycki can be reached at paul.rozycki@mcc.edu.

You must be logged in to post a comment.