By Jan Worth-Nelson

When Flint native filmmaker Michael Ramsdell got to know boxer Taylor “Machine Gun” Duerr at the Brighton gym where they both worked out, Ramsdell was coming off his last film project, a documentary about baseball star (also a Flint native) Jim Abbott.

Ramsdell had loved doing a sports-based story, and he wanted to do another one. What he didn’t know at first, though, was that Duerr’s story presented a radically different, darker challenge: the boxer was a heroin addict.

That story — what Ramsdell depicts as the boxer’s heroic struggle with addiction and the need to destigmatize those with substance use disorder (SUD) — became the heart of the film, Ramsdell’s sixth and, he says, his most accessible.

“It was a boxing film that carries the story line, but it was addiction that became the reason it was made,” he says.”The film only works because of how honest he was willing to be on camera.”

A Flint audience can see the film, “We Can Be Heroes,” at 7 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 19 at the Capitol Theatre. The screening will be preceded at 5:30 by an exhibit by local artists in recovery. A panel discussion, including Taylor Duerr himself, will follow.

The screening is free but tickets are required, available here.

The topic of “We Can Be Heroes” is vitally relevant to Genesee County, where there were 184 reported overdose deaths in 2020, and 155 overdose deaths between May 2021 and April 2022, according to Michigan’s Overdose Data to Action Dashboard.

Genesee County has the third highest rate of opioid deaths in the state, behind Wayne and Macomb counties, according to the site.

During their early acquaintance, Duerr was up and down with addiction, still “struggling pretty hard,” Ramsdell says. “He’d be at the gym four or five months, he’d take a fight, he’d be doing great, and then he’d disappear and they’d find him on a street corner in San Francisco, homeless, 50 pounds lighter.”

But as a “hero” narrative, “he’s a great story,” Ramsdell says. “The thing that makes a documentary work is that whoever is the heart of the story, they have to able to carry it, they have to be able to articulate it, the camera has to love them.”

Duerr “checked all those boxes,” Ramsdell recalls. And when Ramsdell approached him to make the film, “He was willing. And the amount of courage it took to go through it — I was up his butt with the camera for a long time.”

“The juxtaposition of addiction and boxing was fascinating to me,” Ramsdell says. “I had no idea what role addiction would play…but addiction showed its head in so many ways.

“Commonly people think of addicts as weak, or as lazy, or they don’t care about anybody else, or they can’t handle the tough part of life,” Ramsdell says, but Duerr cuts through all of those misconceptions.

Son of longtime Flint legends and community pillars Dick and Betty Ramsdell, the filmmaker attracted to his project team two prominent Flint leaders as producers — financial advisor and talk show host Gary Fisher; and Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, an ear, nose and throat physician who has played key roles in many Flint causes. Crucially, Mukkamala is immediate past chair of the American Medical Association (AMA) board of trustees and chair of the AMA Substance Use and Pain Care Task Force. Fisher and Mukkamala both supported the project financially.

The three convened at Totem Books recently to talk about the film and the issues it explores.

“Mike is a great story teller,” Fisher says, “and I knew he would tell it in a way it would be compelling. His whole career has been dedicated to taking action on really hard core topics.”

Mukkamala says “We Can Be Heroes” offered an intersection of two aspects of his life — Flint and health care. He had participated in funding one of Ramsdell’s earlier documentaries, When Elephants Fight (2015) about conflict minerals in the Congo.

But this project’s relevance to Flint particularly drew the physician in.

“It’s another example of Mike’s courage to go out and try to make a difference by telling a story. This is not as a Warner Brothers feature,” Mukkamala says.”This is closer to home. So many problems come from addiction…we like to blame politicians and government, but it’s hard to talk about…when it comes to addiction…the issues get stigmatized.”

At the national level, in meetings in Chicago and Washington D.C., at the “10,000-foot level” as Mukkamala describes it,” a problem can be studied academically,”

But “to be looking at the story of an individual that’s suffering from substance use disorder, and the consequences it has for them, the way it impedes somebody’s hopes for themselves, — that is a powerful way to guide us while trying to figure out an overarching strategy,” he says.

“This isn’t something that is an inner city problem,” Mukkamala observes.. “We know now from the data that it’s all over — suburbia, inner city — it’s an equal opportunity danger.”

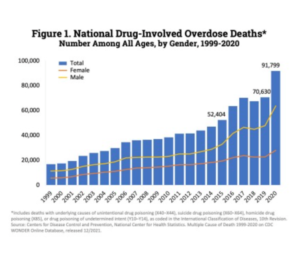

Deaths are at an all-time high [close to 108,000 this year, up from fewer than 20,000 in 2000] And despite the widespread reach of the epidemic, Mukkamala notes, “Demographics are changing — even a few years ago white populations had the highest death rate, but now it’s more black and Hispanic” as opioids became more accessible.

Mukkamala also asserts sources of the opioids have shifted somewhat, from physician prescriptions for pain relief to street sources — particularly for illegal fentanyl.

The physician community has changed its practice, he says, filing prescription information on a readily accessible data base, called the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), providing safe disposal methods, and being careful about giving patients a large supply for pain, for example, when they may only need it for two days. He reports there has been a 40 percent reduction since 2017 in the number of opioid prescriptions written, yet deaths have continued to soar.

Noting that research suggests a physiological link to the risk of opioid addiction, Mukkamala said about 95% of patients take opioids the way they’re intended, but 5% have a biological response that makes them crave more.

“We Can Be Heroes” team convening at Totem Books (from left, film maker Michael Ramsdell, Gary Fisher, Bobby Mukkamala (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Duerr talks about that insidious attraction eloquently, Ramsdell says. “It was better than anything, but then — once it gets you, it’s the devil. It’s in the DNA somehow.”

Some doctors prescribe more pain relievers than needed after surgery, and the unused pills in a medicine cabinet can create temptations or risks to children or others in the home, Mukkamala points out.

He said the number of health care providers checking the PDMP database is six times higher than when it first became available.

Several other health care issues play into the story, Mukkamala says, such as accessibility of treatment for prisoners with substance use issues, and addressing a lack of “mental health parity” in insurance coverage and treatment for substance use disorder (SUD) issues.

Mukkamala says “when addiction rises to the level of needing medical health attention,” mental health parity — assuring equal support for mental health treatment — can be elusive.

“If you go to a local hospital today with a hip that needs to be replaced, you can get it done in a week or two. But if you go with a substance use disorder (SUD) you’ll be sitting in the hospital for a week just trying to find a place to land for in-patient therapy, waiting for a place to land. The practical side of it is that the resources aren’t there.”

As he summarizes it, help is generally available for “fixing broken bones and blocked arteries, but it’s not there to help somebody with their mind.”

Underlying the Taylor Duerr life story and what it implies for the world in general, Ramsdell says he feels, “there’s a psychological and mental epidemic” in the land.

“There is so much hopelessness and confusion in this country — in our youth and our adults — everybody has a fucking opinion about how everybody should be doing something different,” he says. “Everything is so specifically categorized into right and into wrong, with no margin for error, with no support,

The “empathetic connection is completely void,” he says. Describing how he himself engages in meditation twice a day, “I still find myself asking, what does this mean, what is this about, where do I need to do better, who do I need to comfort, who will comfort me…incredibly important human questions.

“In other words, the most important human questions. We don’t talk about it as a culture, we don’t acknowledge it as a culture, and then when you turn to something that can comfort you, something that we don’t agree with, you get put aside as an addict.

“In that case, you’re either for-profit because we can sell you something to help you try to get over it, or you’re for-profit because you end up going into the prison system. Or maybe somebody makes a movie about you.”

Once you look at the world through the lens of empathy, Ramsdell asserts, “There is nobody in the world you can’t empathize with, there’s no human issue that isn’t related to somebody trying to fill a void in their life — food, political ideology, heroin, a desire to make more money than the next guy.”

Ramsdell says his job as a filmmaker is three-fold: to create understanding, hope and action.

“That’s my whole business model,” he said, “to bring intellectual and empathetic understanding of an issue, to offer hope that it can be overcome, and to suggest actions that you can take. That’s how you create change.”

Fisher says Taylor Duerr is an example that “you can be really strong and still get shot down — and then to fight back.

“If the void in somebody’s life gets filled by the pill that makes you feel good, not the brotherhood of the football team, or the debate team, or kids you grew up with in the neighborhood, the community has a problem.”

There is one upside in efforts to get ahead of problems that could lead to addiction, Mukkamala says. Flint has become a national model for helping children manage anxiety: the Crim Foundation is offering “mindfulness” training in every public school in the district.

Fisher says the theme of the film he most strongly endorses is its attempt to ameliorate the stigma associated with substance use disorder.

“When you get people thinking about all this, when you then cause people to take action, you save lives,” he says.

“Until we have these conversations at a community level, there won’t be a community response,” Mukkamala says. “Yes, it’ll be individual people that understand and try to have an impact, but until it’s something that the health care system, the Chamber of Commerce, law enforcement, the legal system, the educational system are all on the same page at a baseline of what best practices are, then that would be a good outcome.

“But it starts with seeing what it does with one individual. Numbers might be a fleeting thought. in my mind, but when you hear the story of an individual at this level, seeing it through his eyes is an eye-opener.”

Ramsdell says a documentary of this nature characteristically costs $2 million to $3 million. But because he was able to make it with his own gear and his own time through his Under the Hood Productions, he managed the production for significantly less.

Both Mukkamala and Fisher absolutely believe their investment is worth it.

“If this movie has an impact to prevent overdose, which I full expect it to,” Mukkamala says, “either in having people not following down that path to addiction or helping them find safety in social understanding of their problem, maybe they will not end up in an ER, blue and cyanotic…

“Is it not worth the investment of spreading the word about substance use disorder? Social awareness is worth investing in. Prevention is overall so much cheaper,” he says.

“This film is going to save lives,” Fisher says. “There will be people breathing 10 years from now who wouldn’t be breathing if we didn’t make this film.”

“Taylor is a hero,” Ramsdell concludes. “It takes heroic effort to deal with issues of this size…There are a lot of broken people and we can heroically address them.”

For more help

Many local resources and support services are available to Genesee County residents who may be experiencing substance use-related issues, according to Kelly Ainsworth, project manager of the Greater Flint Health Coalition (GFHC).

She said anyone interested in seeking support can call the 24/7 Quick Response Team (QRT) warmline at (810) 624-1177 or text (810) 835-4288 to speak with a state certified Peer Recovery Cooch. The QRT is a collaborative initiative of the Greater Flint Health Coalition and New Paths, Inc., in partnership with local hospitals, first responder agencies, and community-based organizations. To learn more about substance use and mental health resources available through the Greater Flint Health Coalition, visit www.KnowMoreGenesee.org.

EVM Consulting Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.