By Harold C. Ford

Five years after the merger of two Flint congregations – one predominantly white and located in the center of Flint, the other a Black congregation that left its church home near Flint’s north side – the co-pastors of Every Nation Assembly of God Church remain committed to the union.

“We never look back,” said Every Nation Co-Pastor Michael Stone, who led his congregation’s departure from its former Beecher, Mich. house of worship, Power of God Ministries, to their new home at Every Nation.

“Racial reconciliation has been a big part of mine and my wife’s focus here,” added Every Nation Co-Pastor Tom Mattiuzzo. “It hasn’t been everybody’s cup of tea.”

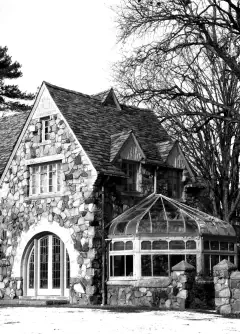

Until 2019, Mattiuzzo was the sole pastor of the former Riverside Tabernacle Assembly of God Church in Flint’s Central Park neighborhood — now Every Nation Church. The building is sandwiched between the city’s downtown district and University of Michigan-Flint campus to the west and Flint’s Cultural Center and Mott Community College to the east.

“I [became] so tired in this town of going to all-white funerals and all-Black funerals,” Mattiuzzo told East Village Magazine (EVM) in late May. “We’re all going to heaven together, we believe, but yet we can’t worship together and serve together.”

Segregated Sundays in a segregated city

In 1964 American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. famously observed that “11 a.m. Sunday is our most segregated hour.”

His observation remains largely true today.

A 2016 report by Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) entitled “Racial Segregation in the Church” found that “86 percent of American churches lack any meaningful racial diversity.”

A May 2023 Axios report that polled 5,872 adults reconfirmed EJI’s finding: “The vast majority of U.S. churchgoers … report that they belong to congregations where most people are of their race or ethnicity…”

A visit to local houses of worship in Genesee County would likely confirm the same findings. After all, Flint is still evolving from its status as one of the most segregated U.S. cities of the 20th century. As Andrew Highsmith wrote in his book, “Demolition Means Progress”:

“By the close of the 1930s, the widespread use of restrictive covenants [in real estate] had helped make Flint the third most segregated city in the nation, surpassed only by Miami, Florida, and Norfolk, Virginia.”

“Southern city”

Mattiuzzo discovered vestiges of Flint’s racially segregated history when he and his wife migrated from Buffalo, N.Y. to Flint in 1992.

“I was surprised by the ‘southernness’ of Flint, by the southern culture of Flint … the racial equations in Flint,” Mattiuzzo said. “I didn’t foresee that Flint would be such a southern city.”

That included the Flint church – Riverside Tabernacle – that hired Mattiuzzo as its new pastor.

“Riverside Tabernacle was exclusively white at that time. There were no Black families in the church at all and most of our families didn’t live in Flint any more,” he said. “They lived in Grand Blanc … Swartz Creek … Davison … Fenton … Clio. They would come pulling in Sunday morning, lock their doors, run into the church, run back out of the church, and lock their doors and get out [of Flint] as fast as they could. For some years we were pretty much a suburban church meeting in downtown Flint.”

Planning for change

“If we don’t change, we don’t grow,” wrote the American author and journalist Gail Sheehy. “If we don’t grow, we aren’t really living.”

About 25 years ago, according to Mattiuzzo, Riverside Tabernacle began planning to change the incongruent relationship between the urban setting of its building and its white, mostly suburban membership.

“We started leaning into the city [of Flint] more,” Mattiuzzo recalled. “We started seeing some African American adults … coming to the church …[who] came in and saw people who looked like them, who were part of our church family and well respected.”

Mattiuzzo and his church leadership team helped grow African American membership at Riverside Tabernacle to about 30 percent.

“As we did that, it wasn’t everybody’s cup of tea,” Mattiuzzo repeated. “But there are lots of suburban, white churches they can go to.”

“We became friends”

Later in the 1990s, Stone’s then-Power of God Ministries and Mattiuzzo’s then-Riverside Tabernacle began partnering.

“We have, over the years, partnered with Pastor Tom, using his facility [Riverside Tabernacle] … the fellowship hall or the sanctuary,” Stone explained. “We became knowledgeable of each other; we became friends.”

Over time, the partnership deepened.

“I would shut down my church once a month,” Stone explained, when his congregation would participate in Sunday morning worship service at Riverside instead.

Mattiuzzo acknowledged the sacrifice made by the Power of God Ministries congregation as part of the merger.

“It takes a lot,” he said, “because when you close up your own service … that costs money [as] you don’t get the offering you get in our own church.”

Michael Stone (left) and Tom Mattiuzzo (right) are Co-Pastors of Every Nation Assembly of God Church in Flint, Mich. (Photo by Harold C. Ford)

Creating “a church that looked like heaven”

The pastors’ partnership eventually morphed into talks of merger.

According to Stone, the idea of a merger was initially promoted by Beau Norman, one of his three personal pastors. After a lunch conversation with Mattiuzzo, Norman advised Stone to connect with him.

“You and Pastor Tom need to get together … maybe you guys can hook up,” Stone recalled Norman saying.

Two years of inaction followed until Norman asked Stone if he’d been in touch with Mattiuzzo, which spurred Stone and Mattiuzzo to start serious talks about a merger.

“That’s where it began,” Stone recalled. “We sat there and talked about, ‘How could we make this work? … Wouldn’t it be nice if we created a church that looked like heaven?’”

Norman recommended a Canadian model of co-pastoring that divided areas of responsibility for managing a church into “pillars.” Stone and Mattiuzzo agreed to manage three pillars each as co-pastors, with each pastor having input on the other’s pillars, too.

A consultant assisted the newly-created Every Nation Church during the initial phases of the merger, according to the co-pastors. The consultant met separately with stakeholders at Power of God Ministries and Riverside Tabernacle.

“He [the consultant] was really important,” said Alan Lynch, a former member of Riverside Tabernacle and current member of Every Nation Church.

The consultant told merger aspirants “it’s like a marriage,” Linda Wortham, former Power of God Ministries member and current Every Nation Church member, told EVM.

“You got to learn how to work it together,” she recalled the consultant saying.

Challenges

“We’ve [Riverside Tabernacle’s congregation] had to accommodate and make room for other ways of doing things,” Mattiuzzo said of the merger. “They’ve [the Power of God congregation] also had to accommodate and make room for other ways of doing things.”

Mattiuzzo added that the diminishment of pastoral autonomy has been a major trial for both he and Stone in the merger.

“One of the challenges we’ve faced is the reality … neither one of us makes unilateral decisions,” Mattiuzzo said. “All of us are less now than we were … in terms of church decisions, but we’ve both become more,” he added.

Stone and Mattiuzzo ultimately agreed upon a 50-50 formula for sharing of the pulpit on Sunday mornings, with exceptions allowed for guest ministers and special occasions.

“We try to come into every day without ego,” Mattiuzzo said. “Every decision, we come to each other, we discuss it … the decisions are made together.”

A second significant challenge of merger was crafting church governance documents, namely Every Nation’s new constitution and bylaws. That process, undertaken by a 20-person board with equal representation from both former congregations, is now more than 90 percent completed, the co-pastors said. Further, nametags and added signage at the Every Nation campus have helped resolve issues of unfamiliarity.

The result?

“Together with these beautiful people,” Stone said of his and Mattiuzzo’s congregants, “we’re growing a church.”

“It’s going to work”

Lynch told EVM that he and his wife had been church-shopping for eight months after moving to Flint from Minnesota.

“We found Riverside because … in the first sermon,” Lynch recalled, “Pastor Tom said, ‘We’ll know that we’re a church in the City of Flint when we look like the City of Flint.’”

I was praying and I thought, ‘God wouldn’t it be great if you could bring a Black and a white church together?’” Lynch recollected. “Two months later, Pastor Tom said Pastor Stone had approached him and said, ‘I think we can do something better together.’”

“In my mind, it was a done deal,” Stone said of those early discussions. “We’re going to merge, and it’s going to work.”

Wortham had followed her son, a musician, into the Power of God Ministries, where she evolved into the role of praise team leader.

Wortham’s biracial mother, whom she reverently remembers as “my foundation,” helped her to reflect deeply about the possibility of merger with a church that was about 70 percent white at the time. “

She’s the one that made me think about it,” Wortham reflected.

“Is this my church?” Wortham said she wondered at the start of the merger. “But we worked that out really quick.”

She said she came to think, “This is your church, feel at home, do what you have to do.”

Ultimately, Wortham said, “the merger was a good thing.”

“What heaven will look like”

It was Mattiuzzo’s turn in the pulpit on May 19, 2024, Pentecost Sunday, when this writer visited Every Nation Church.

The church’s large, modern, half-circle sanctuary featured the flags of 18 nations extending outward from the second-level balcony, and the 100 or so parishioners — not counting youth groups and others elsewhere in the church — frequently rose from their seats, sang, and swayed gently to the first 30 minutes of service led by the Praise and Worship Team.

Many, with arms outstretched, softly uttered “Amen” and “Thank you, Jesus.”

Mattiuzzo and Stone were both casually attired. “We’re not trying to be imperial,” Matiuzzo later said, adding, “sometimes a suit and tie can be a barrier.”

Aside from what seemed a well-delivered, smoothly run service, also notable that Sunday morning was Mattiuzzo’s decades-long vision – “We’ll know that we’re a church in the City of Flint when we look like the City of Flint” – seeming rather realized, too.

In terms of race and age, the people in Every Nation’s pews more closely reflected the demographic diversity of greater Flint than any other recalled by this writer.

“You really cannot find something completely comparable to what we’re trying to do,” Mattiuzzo would say later about the merger that led to that experience.

“We think that this thing is going to explode … going to grow, going to be a model,” said Stone.

In closing out the pastors’ interview with EVM, Mattiuzzo summed up a chief success of the merger in his estimation.

“More and more the Power of God [Ministries] people are accepting of me as a pastor, equal to Pastor Stone,” he said. “And I know, more and more, the Riverside [Tabernacle] people are more accepting of Pastor Stone as equal to me.”

However, as both senior pastors approach retirement, the durability of their merger may be tested.

“Neither one of us want to be doing this five years from now,” Mattiuzzo said.

Still, even with the challenges, current and ahead, Stone concluded: “This is a church that probably … look[s] like what heaven will look like.”

This article also appears in East Village Magazine’s June 2024 issue.

You must be logged in to post a comment.