By Jan Worth-Nelson

In 1888, seven upper-class women, all neighbors in what was then considered one of Flint’s most elegant neighborhoods, walked along leafy streets to an early afternoon gathering at 718 Garland. It was the home of Mrs. Sarah Durand, wife of a prominent local judge, George Durand.

The meeting was not just tea and crumpets. The women were intent on forming a club, and they got right down to business. That day, November 14, they handwrote a constitution.

Article I read, “The organization shall be called The Garland Street Literary Club. Its object shall be reading study and mutual improvement.”

Remarkably, 136 years and many societal, cultural, and demographic changes later, the club still exists, making it the oldest continuously meeting women’s group in Flint according to its historian, Mary Ann Cardani. (The St. Cecelia Society also started in 1888, she points out, but it was not a women’s group).

Over time, some of the fancy houses disappeared, the club’s original members died or moved on, and the neighborhood changed, so by the 1920s the group no longer met on Garland Street.

But, perhaps out of tradition and loyalty to the founders — and that late 1800s constitution — each succeeding generation of members kept the club’s name.

–––––

On a recent Monday afternoon, a dozen current members came back to meet on Garland Street for the first time in 100 years.

The return was made possible by the emergence of Queens’ Provisions, a woman-owned wine and charcuterie shop that opened just last year at 421 Garland.

A woman-owned business was unheard of to the club’s original charter members, who were known socially through their husbands’ ventures.

Besides Judge Durand, for example, their husbands included John Hotchkiss, a manager for the Paterson Carriage Company; Dr. Luke Beagle; Zach Chase, a bookkeeper at the Crapo Lumber Company; William Hubbard, owner of a grocery store; Frank Jones, a hatter and travel agent; and Nell Randall, who ran a lumber and coal business.

As upper-class women, Cardani said, the club’s founders could afford “help” in their homes and could leave for a few hours during the day. Yet they were almost wholly defined by their husbands, whose names — Dort, Hasselbring, Nash, and more — would later adorn Flint’s streets and schools. In fact, early members were so defined by their husbands that finding out their own names (instead of “Mrs. William Hubbard,” for example) was a research project of the club in recent years.

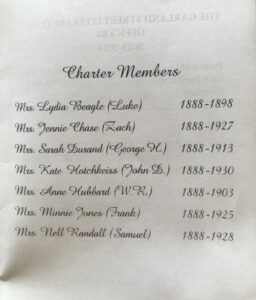

The list of original Garland Street Literary Club members. (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Cardani noted the Garland Street Literary Club founders were not academics, but intelligent women nonetheless limited by their status in life and “tired of knitting and crocheting — they wanted to expand their minds…to improve their knowledge.”

Although it’s now 2024, sitting with today’s members, sunlight streaming over the charcuterie board, wine bottles, and easy chairs of Queens’ Provisions, one can almost imagine that other era.

But things are clearly different today.

Partly because the club has met exclusively during standard workday hours, the membership is almost all older, retired women — a silver-haired circle, noisy with frequent laughter and overlapping conversation.

They are mothers, grandmothers, great grandmothers, aunts and great-aunts. The average age of the club’s members is mid-70s. Cardani is 80, and Michele Talarico, another member, is 75. Caroline Stubbs, member and retired hospice executive, is 74.

Talarico and Cardani both joined in 2013, and the current president of the Garland Street Literary Club, Caroline Boegner, joined in 2018.

Many told East Village Magazine they came on board because of family or neighborly connections. But significantly, unlike the women of the 1880s, they are distinguished not by their husbands, but by their own careers – in health care, education, law, social work – professions unthinkable for the club’s founding members.

They say the club helps them stay connected and keep active minds.

“Once you retire, unless you make yourself visible, you become invisible,” Talarico said. “When I come [to meetings], I feel listened to, I feel valued. I know that I value every single woman in this group.”

The club has never had a male member, and no man has ever tried to join.

“We’re invisible. Why do they want to be invisible?” one member offered in wry explanation during the Queens’ meeting, soliciting laughter from the gathered ladies.

The club’s 13 current members say while their lives are radically different than the founding members’, they still cherish their memory and value the original goals and pleasures of each others’ company to read, discuss, and learn new things.

“Women are looking for something” in a polarized and often isolating age, Cardani said.

“There are not a lot of ways for women to be together and share their lives these days,” added Talarico, a retired educator and former director of youth health advocacy programs.

“The ladies are so interesting…they bring their stories, and their stories are different than my stories, but they’re interested in mine,” she said.

From left to right, Ruth Goergen, Michele Talarico, Mary Ann Cardani, April Baer and Bobbie Goergen attend a meeting of the Garland Street Literary Club on May 13, 2024. (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Barbara Mills, the club’s oldest current member at 86, is a retired teacher of science and English.

”Learning is my life,” she declared. “I love being around women who are inquisitive and who want to know things…that’s always been important to me.”

Mills recently presented a paper, roundly praised by other members, on Aleda Lutz, a little known World War II nurse who was killed in action.

According to club rules, all members must present a research paper and host the group once every two years.

Originally, Cardani said, women presented on different countries of the world. Over the decades, though, topics have become much more varied — the club’s current theme, selected by group vote, is “Women Warriors and Peacemakers” — and the meetings have been held outside of members’ homes from time to time.

Still, the group meets religiously at 1 p.m. on the second Monday of the month, and dues are $10 per year. During the pandemic, members managed several Zoom gatherings, though Cardani said a few months ultimately had to be missed.

In 1988, the late Alice Lethbridge, a long-time Flint Journal reporter, wrote a history of the group for a University of Michigan-Flint archives publication.

In the introduction to Lethbridge’s history, Marie S. Crissey noted that “since admission to members was by recommendation of active members, it was natural that new members similarly came from the community elite and represented the somewhat more ‘intellectual’ element. The fact that the Garland Street Literary Club was not purely a social club, but required that the members present a paper of some merit in at least alternative years, also formed an obstacle to some aspirants.”

The club, then, was “a product of its times and its setting. That it has survived a full century attests to its vitality, [and] is evidence that it has filled a needed role in the community…” she concluded.

“A History of the Garland Street Literary Club” by late Flint Journal reporter Alice Lethbridge. (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson)

Mary Jo Kietzman, an English professor at UM-Flint, is helping the group consider its future, as members say they understand that if they are to survive they’ll have to recruit new women.

With several others, Kietzman is designing an “adjunct group” for younger and working women to reflect greater diversity. The adjunct group would meet in the evening and still pursue some of the group’s goals.

The club’s recent gathering was a meet-and-greet with some of those potential new members — though the youngest to attend was 56, and current members noted they are still aiming for more racial diversity.

Clara Blakely, the only woman of color to attend the meet-and-greet, said that’s at least a start.

“To have diversity you have to have intention,” she told East Village Magazine. “A lot of folks don’t want to go someplace where nobody else looks like them, but I don’t care.”

Kietzman and the club’s veteran members said they are paying attention and hope to make the next iteration of the club more welcoming to younger women and women of color.

“Self-education was a big deal in the 19th century and early 20th century America,” Kietzman said. “It was recently touted as one of the defining features of the good life in the Midwest.”

Noting that in a recent class, only two of her students had heard of Flint’s 1936-37 Sit-Down Strike, Kietzman said, “The question remains: what ought to be carried forward out of Flint’s history? There is so much at risk of being lost.”

“It is a big problem that we are losing civic associations and fraternal lodges,” she continued. “What is replacing them?”

The women of the Garland Street Literary Club hope their so-far remarkably durable history will provide one ongoing option.

Considering that the meeting at Garland Street was like “coming full circle,” with the club’s history, member Jeanette Mansour concluded, “We’re capable of looking at the past, but also looking forward.”

This article also appears in East Village Magazine’s June 2024 issue.

You must be logged in to post a comment.