By Gordon Young

Flint isn’t exactly associated with fun and games. So it’s fitting that a new board game centered on Vehicle City tackles a seminal event in its history that was defined by violence, corporate greed, and worker revolt.

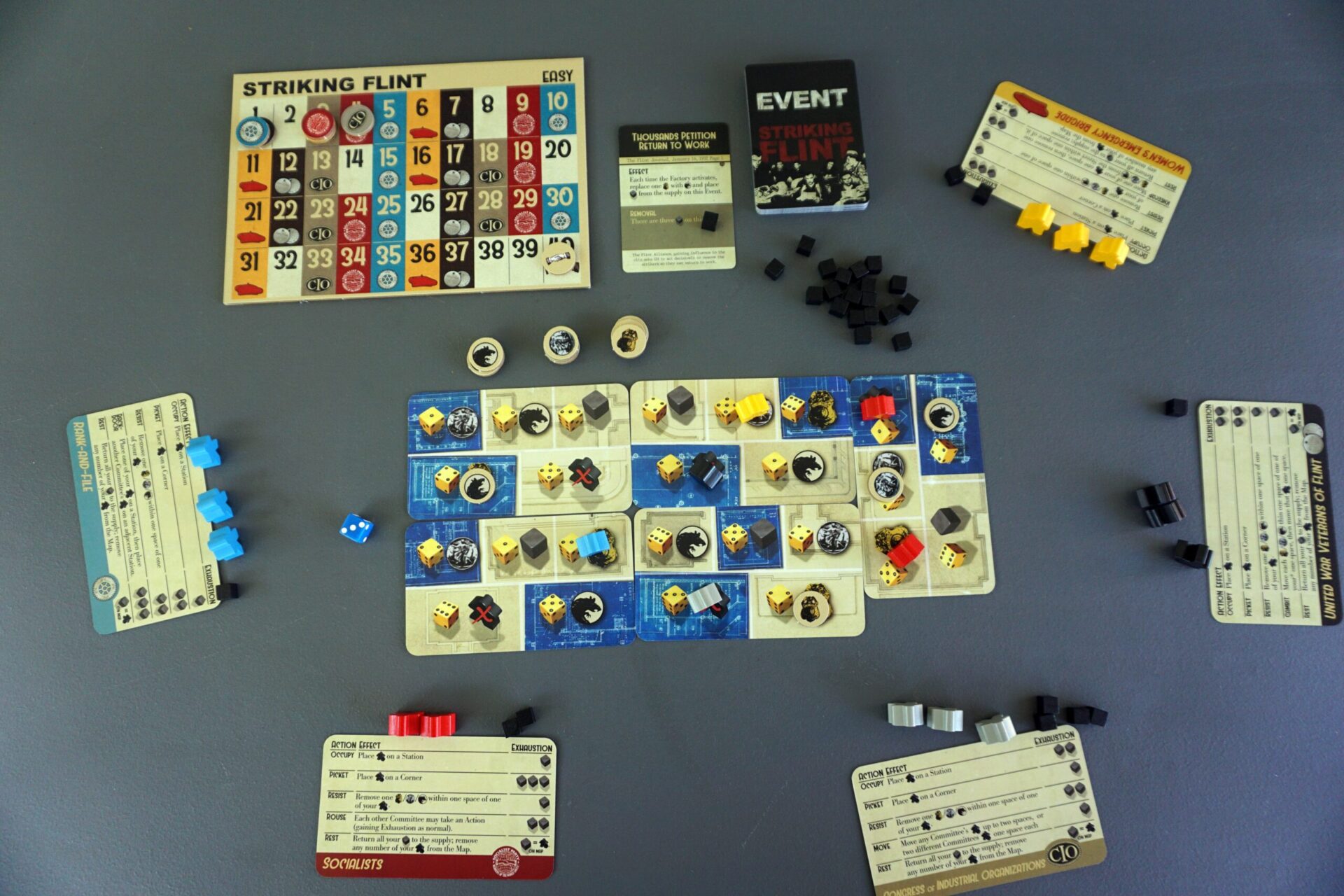

Striking Flint is the creation of Flint native John du Bois and immerses players in the drama of the 1936-1937 Sit-Down Strike, a confrontation that established the United Auto Workers union as a force that would reshape American life.

“We’re still fighting this idea that unions are just trying to get more money out of their companies for less work,” du Bois said. “The big message I would like people to get out of Striking Flint is that workers put themselves at great financial and physical harm. They really had to fight tooth and nail to get all these things we take for granted now.”

To state the obvious, this is not Candy Land. Board games for intense hobbyists like du Bois are multilayered and often reference historic events. They require more dedication than a quick game of Clue, and the instructions won’t fit on the back of the box.

Striking Flint is a cooperative game, meaning players are all on the same side, working together against a common adversary — the General Motors Corporation (GM).

A deck of event cards based on pivotal moments in the strike drives the action. Players control various worker committees that have their own advantages and disadvantages in the battle against GM. But management has resources of its own — pliant police and city officials, vast financial resources, hired thugs, and a sympathetic press.

“You’ll need to work together to weather the forces arrayed against you – fending off attempts at eviction, the effects of exhaustion, and the presence of strikebreakers – while occupying factories in the plant complex,” the publisher’s game description reads.

As such, Striking Flint probably won’t appeal to anti-union, pro-management types. (Monopoly would be a better choice for anyone who would happily cross a picket line.)

The game grew out of du Bois’ determination to honor his local roots. He was only two when his family moved to Flint in 1984 after his father, an electrical engineer, took a job at AC-Delco. They lived in Mott Park near the municipal golf course.

“One of my father’s great frustrations is that we moved within two blocks of a golf course, and I hated golf,” du Bois joked.

He didn’t play many board games while growing up. As a student at Powers Catholic High School, he was more interested in choir and the school’s annual musical theater productions. But after graduation in 2000, he discovered Dungeons and Dragons as a student at Eastern Michigan University.

More specifically, du Bois gravitated to a variation called Living Greyhawk that explored a specific campaign fantasy world. He was soon writing and editing for the campaign creators.

“And then I got married to someone who didn’t want to play Dungeons and Dragons,” he said. “We started playing board games instead.”

Du Bois began a career as a speech pathologist and settled in Troy, Mich. with his wife and two children. In his spare time, he channeled his energies into creating his own board game.

John du Bois, Flint native and creator of Striking Flint (Photo courtesy John du Bois)

The first result was Avignon: A Clash of Popes, set in 1378 when rival popes vied for control of the Catholic church. It’s the sort of game you might expect from a Catholic school kid with a love of history.

“Avignon is very fast and quite simple, yet there’s some room for strategy,” according to a review in Games Magazine. “With a cunning move a game can be finished in minutes, but that’s part of the appeal.”

When du Bois started thinking about his next project in 2015, there was an ongoing discussion across the country and in the gaming world about diversity. Most games were dreamed up by white men, and du Bois contemplated what his responsibilities were as a creator.

“Could I justify pitching games to become yet another white man making board games?” he wrote in a designer diary on Board Game Geek, a popular online forum. “What could I contribute to games that nobody else, or very few people, in the industry can contribute?”

He chose to focus on the local history of the place where he grew up, the place that shaped him, and the Sit-Down Strike had all the drama and significance he needed.

As du Bois refined his idea, he created various prototypes.

In an early version, he used LEGO figurines as stand-ins for various pro-union strikers. Thor was a “brawler” and Abraham Lincoln was a “rabblerouser,” to name a couple. The various corporate agents who opposed them got a less flattering moniker — “scabs.”

He submitted an early version of Striking Flint to a gaming contest, and the feedback was positive but called for more details related to specific events rather than broad themes. Du Bois intensified his research on the strike, reading books by Sidney Fine, Ted McClelland and others; listening to oral histories of sit-downers; and reviewing contemporaneous press accounts. He spent hours poring over microfiche in the Thompson Library at UM-Flint for details that would make the game more realistic.

While fine-tuning Striking Flint, du Bois worked simultaneously on another idea that he developed after suffering a severe concussion in a 2015 car accident: a solitary game related to his rehabilitation process called Heading Forward.

Instead of a fantasy world, the game is decidedly realistic.

“To win, you must relearn and develop skills, achieving goals in at least three different areas in the time you’ve been allotted by your insurance company,” according to the publisher’s description of the game, which came out in 2022. “Fail to do so, and they will discontinue payment, resulting in your loss.”

When he resumed work on Striking Flint, du Bois realized that the goal of the strikers was really to just hold out. It was all about survival, and the game needed to reflect that premise.

“The UAW won the Flint strike simply by not losing for long enough,” he wrote in his designer diary. “Once GM realized they were losing more money with these factories shut down than it would cost to work with the union, they came to the negotiating table. I needed to do the same thing; to win, the players just needed to last until a certain period of time was over.”

As he put the final touches on Striking Flint, which premiered this year, he couldn’t help noticing connections to conflicts happening around him as graduate assistants went on strike at the University of Michigan and students protesting the war in Gaza were being forcibly removed by police at some colleges.

“I literally can’t stop seeing parallels to what was experienced in Flint in 1937 and what is happening today,” he wrote. “I do hope that I’ve created enough verisimilitude that people buying and playing it notice the fights they’re simulating on their tables aren’t just an artifact of history — they have an appearance of truth and accuracy that has echoes in events today throughout the country and the world.”

Gordon Young is a journalist who grew up in Flint’s Civic Park neighborhood and attended St. Mary’s grade school. He is the author of “Teardown: Memoir of a Vanishing City,” and his work has appeared in the New York Times, Slate, Politico and numerous other publications.

You must be logged in to post a comment.